Money And Wealth In Islam : The Root Of All Evil?

The idea that ‘money is the root of all evil’ actually has no basis in Islam. However, as we live in a highly commercialized world, it has entered the mindset of many people wanting to live a life of simplicity and asceticism for a variety of reasons. So if such a notion doesn’t have a basis in Islam, what does Islam actually say about what the nature of our relationship with money should be?

Many people often struggle with the concept of wealth allowing their emotions and sometimes, preconceived conclusions to create, in their view a ‘conflict’ between Islam and money – a conflict that may lead us to believe that wealth will sabotage our path to ‘piety’ and so we end up allowing what we understand to be an ‘Islamic attitude’ to actually sabotage our path to being financially secure. People often don’t know how to react when they see Muslims having excess amounts of wealth whilst at the same time being good Muslims. More often than not, we assume the worst when someone has been blessed with wealth and is seemingly ‘religious.’ It seems that our own life experiences also play a role in determining our personal and individual ‘wealth story;’ a script which is created and fashioned by our own unique life experiences in our own wealth journey.

In our communities, we seem to have two extremes; we have people who say that poverty is the ideal, making us think that we should aim to be poor! A lot of times people who bring up this extreme will cite the fact that there were poor people in our history who were great people, which is no problem, but even those people who financially may not have had money in their hands still reached for the highest possible standards in whatever they did.

Muslims who think poverty is the ideal, will cite Umar ibn al Khattab  and say that he was poor and lived a simple life1, which is true to an extent because he didn’t live an extravagant life, but that is not to say Umar

and say that he was poor and lived a simple life1, which is true to an extent because he didn’t live an extravagant life, but that is not to say Umar  didn’t have money! Umar

didn’t have money! Umar  was one of the greatest leaders of humanity who ruled vast lands in his era. He had all the riches he needed, yet he didn’t spend it on himself; choosing instead to use it to take care of his people. That’s the difference – we should aim to have the wealth but not spend it extravagantly on ourselves and then just end there. The whole purpose of having money and building wealth is to be able to benefit yourself and others with it. Who will sponsor orphans if we aim to be poor, who will build mosques and pay off the qard hasana that some of our mosques need to pay back, who will support the poor in our community if we aim to be poor and have no zakat and sadaqah to give?

was one of the greatest leaders of humanity who ruled vast lands in his era. He had all the riches he needed, yet he didn’t spend it on himself; choosing instead to use it to take care of his people. That’s the difference – we should aim to have the wealth but not spend it extravagantly on ourselves and then just end there. The whole purpose of having money and building wealth is to be able to benefit yourself and others with it. Who will sponsor orphans if we aim to be poor, who will build mosques and pay off the qard hasana that some of our mosques need to pay back, who will support the poor in our community if we aim to be poor and have no zakat and sadaqah to give?

But then there is the other extreme – some people only focus on money regardless of where it comes from, whether it’s haram or halal. They might even forget entirely about building a home in paradise. For these people, it’s all about money and unfortunately, we see these people a lot in our times; those who make a lot of money, spend it like crazy and post things on social media to get attention – that’s also not the ideal situation Muslims should aim to be in!

Let us now move on to what Islam actually teaches us about wealth and money.

What Does the Quran Say About Wealth? (a) The Link Between Money & Worship:There are many places where Allah (the Most High) mentions the word rizq (provision, sustenance); which we also translate to mean wealth even though rizq is a more comprehensive term. Let us look at a selected few ayaat (verses):

Allah  says in the Quran:

says in the Quran:

“And I have not created the jinn and mankind except that they worship me.” [Surah Adh-Dhariyat; 51:56]

He then informs us that in the following ayah:

“I do not desire any provision from them, and I do not wish them to feed me.” [Surah Adh-Dhariyat; 51:57]

Because:

“Verily, God, He is the provider, endowed with steady might.” [Surah Adh-Dhariyat; 51:58]

Here there is a link between money and worship; in other words, Allah  is telling us that the reason why He

is telling us that the reason why He  created mankind and jinn (solely to worship Him alone) and that He doesn’t want anything of food or money from us, because He is the Provider and He will provide for us (his creation).

created mankind and jinn (solely to worship Him alone) and that He doesn’t want anything of food or money from us, because He is the Provider and He will provide for us (his creation).

Allah  also commands us to:

also commands us to:

“And enjoin prayer upon your family [and people] and be steadfast therein. We ask you not for provision; We provide for you, and the [best] outcome is for [those of] righteousness.” [Surah Taha; 20:132]

Here Allah  commands us to establish the prayer with our families. Again He informs us that He isn’t asking us for provision, rather it is He

commands us to establish the prayer with our families. Again He informs us that He isn’t asking us for provision, rather it is He  who gives us the provision and sustenance. Again there is a correlation between worship and sustenance or money because as humans we are weak and one of the primary distractions to worship is money! One of the main reasons ‘common people’ give about why they are not so ‘religious’ is because they want to enjoy life, and spend their wealth after making it; but here Allah

who gives us the provision and sustenance. Again there is a correlation between worship and sustenance or money because as humans we are weak and one of the primary distractions to worship is money! One of the main reasons ‘common people’ give about why they are not so ‘religious’ is because they want to enjoy life, and spend their wealth after making it; but here Allah  is saying: don’t be distracted by money, I’m not asking you give me money, if you worship me, I will give you money (provision)!

is saying: don’t be distracted by money, I’m not asking you give me money, if you worship me, I will give you money (provision)!

Allah  created us and knows our true nature; that we all have a natural inclination for money and the need to enjoy it. He

created us and knows our true nature; that we all have a natural inclination for money and the need to enjoy it. He  is therefore telling us that despite this ‘natural’ desire for wealth and provision, we shouldn’t become distracted because:

is therefore telling us that despite this ‘natural’ desire for wealth and provision, we shouldn’t become distracted because:

“Who is it that could provide for you if He withheld His provision?” [Surah Al-Mulk; 67:21]

In this verse, Allah  challenges the people; if He withheld the rizq (sustenance), is there any other being who can provide them rizq? Truly it is only Allah

challenges the people; if He withheld the rizq (sustenance), is there any other being who can provide them rizq? Truly it is only Allah  Who has the power to provide us with provision and sustenance!

Who has the power to provide us with provision and sustenance!

In many ayaat (verses) Allah  commands the believers to enjoy the blessings that He has provided for them. Allah

commands the believers to enjoy the blessings that He has provided for them. Allah  says:

says:

“And [recall] when Moses prayed for water for his people, so We said, “Strike with your staff the stone.” And there gushed forth from it twelve springs, and every people knew its watering place. “Eat and drink from the provision of Allah , and do not commit abuse on the earth, spreading corruption.” [Surah Al-Baqarah; 2:60]

Here Allah  is telling the Muslims to eat and drink but not to misuse the abundance of Allah

is telling the Muslims to eat and drink but not to misuse the abundance of Allah  and not to spread corruption.

and not to spread corruption.

He  also says that it is He who:

also says that it is He who:

“… who made for you the earth a bed [spread out] and the sky a ceiling and sent down from the sky, rain and brought forth thereby fruits as provision for you. So do not attribute to Allah equals while you know [that there is nothing similar to Him].” [Surah Al-Baqarah; 2:22]

And then tells us:

“O you who have believed, eat from the good things which We have provided for you and be grateful to Allah if it is [indeed] Him that you worship.” [Surah Al-Baqarah; 2:172]

So we are commanded to eat, drink, and earn our sustenance from permissible (halal) means and in doing so we should show our gratitude to Allah  and worship Him alone since it is He

and worship Him alone since it is He  who has provided us the sustenance to enjoy in the first place!

who has provided us the sustenance to enjoy in the first place!

Allah  also says:

also says:

“Say, “Who has forbidden the adornment of Allah which He has produced for His servants and the good (lawful) things of provision?” Say, “They are for those who believe during the worldly life (but) exclusively for them on the Day of Resurrection.” [Surah Al-‘Araf; 7:32]

Here Allah  challenges and refutes those who prohibit any type of food, drink, or clothes according to their own understanding without relying on what Allah

challenges and refutes those who prohibit any type of food, drink, or clothes according to their own understanding without relying on what Allah  has legislated.

has legislated.

Allah  reminds us that the wealth that He has bestowed upon us is not only a blessing from Him

reminds us that the wealth that He has bestowed upon us is not only a blessing from Him  , but also a trial and a test for mankind.

, but also a trial and a test for mankind.

“Your wealth and your children are but a trial, and Allah has with Him a great reward.” [Surah At-Taghabun; 64:15]

He  also states:

also states:

“And know that your properties and your children are but a trial and that Allah has with Him a great reward.” [Surah Al’Anfal; 8:28]

So all of our wealth, possessions, and even our children are a test and a trial from Allah  and to make this test even more challenging, Allah

and to make this test even more challenging, Allah  has created us with the natural inclination to collect wealth. Society has raised the value of wealth high above most worldly commodities to the extent that mankind now judges each other based on wealth. Monetary assets are also used to determine social status because with their presence, power, confidence, and fame increase whereas without it, they are seemingly lost or diminished.

has created us with the natural inclination to collect wealth. Society has raised the value of wealth high above most worldly commodities to the extent that mankind now judges each other based on wealth. Monetary assets are also used to determine social status because with their presence, power, confidence, and fame increase whereas without it, they are seemingly lost or diminished.

?

?

Amr ibn-al-Aas

narrates that the Prophet

said2:

“I want to send you as the head of an army. Allah will keep you safe and grant you booty, and I hope that you will acquire some wealth from it.”

Amr

replied: “O Messenger of Allah

, I did not become Muslim out of love for wealth, I became Muslim out of love for Islam and to be with the Messenger of Allah

.”

Then the Prophet

replied: “O’h Amr, how beautiful is pure money for a righteous man?”

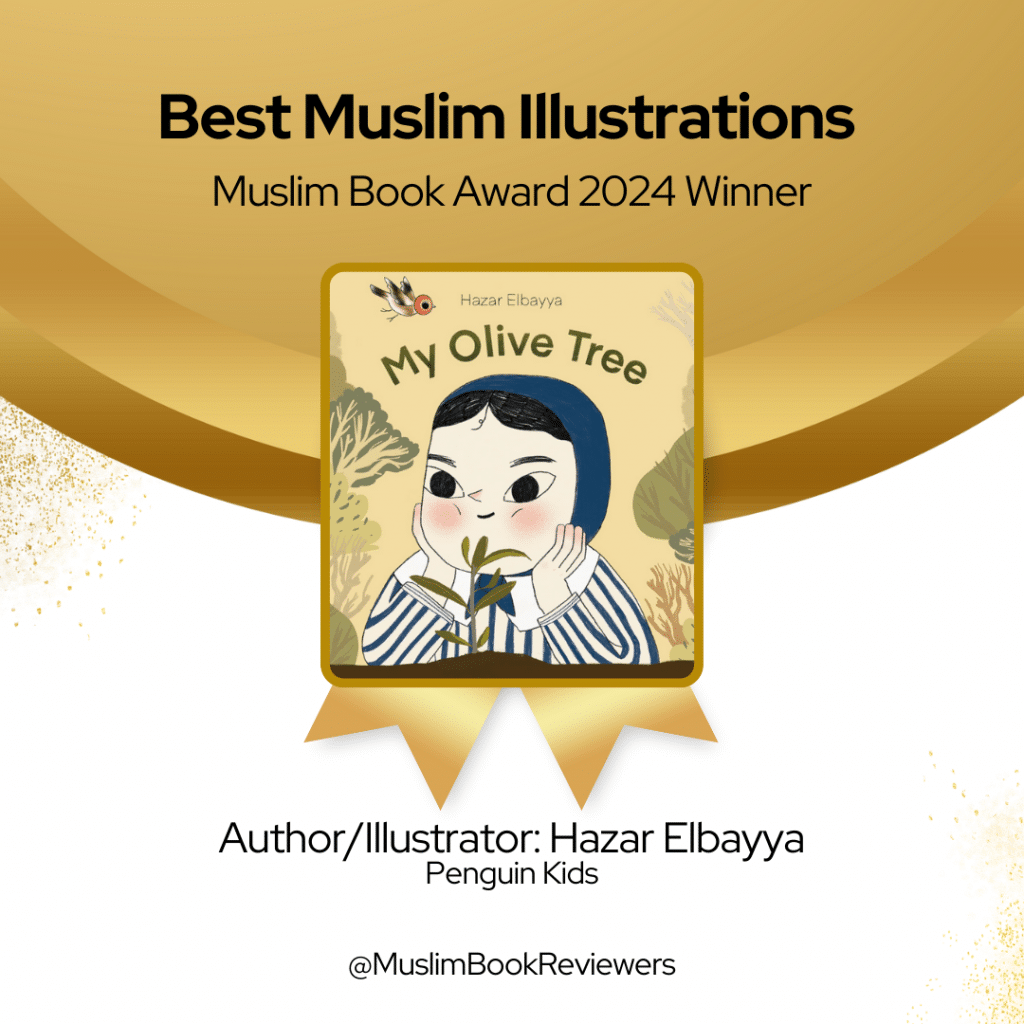

The giving hand is better than the receiving one. [PC: Masjid Pogung Dalangang (unsplash)]

Not only is this incident an indication of Amr’s strong faith and sincerity, but it was as if he felt that he needed to explain why he became Muslim (for the love of Islam and to be close to the Messenger

strong faith and sincerity, but it was as if he felt that he needed to explain why he became Muslim (for the love of Islam and to be close to the Messenger  ). However, the Prophet

). However, the Prophet  explained that halal (permissible) wealth is a blessing when it is possessed by a righteous man. This is because he will spend it in good ways such as sponsoring orphans and widows, calling people to Islam, building mosques and other charitable causes, as well as maintaining dignity for himself and his family, and helping the Muslims.

explained that halal (permissible) wealth is a blessing when it is possessed by a righteous man. This is because he will spend it in good ways such as sponsoring orphans and widows, calling people to Islam, building mosques and other charitable causes, as well as maintaining dignity for himself and his family, and helping the Muslims.

From this hadith, we understand that if a person strives to acquire halal (honest and pure) wealth, this is something praiseworthy that was encouraged by the Prophet  .

.

It is always better to work and earn your money in a halal way, which is a respected and dignified way to live.

The Prophet

said: “The upper hand is better than the lower hand, (i.e. the spending / giving hand is better than the receiving hand); and begin charity with those who are under your care; and the best charity is that which is given out of surplus; and whoever abstains from asking others for some financial help, Allah will save him from asking others and make him self-sufficient.” [Al Bukhari]

Abdullah ibn Umar  also reports the Messenger

also reports the Messenger  was sitting on the pulpit and talking about charity and abstention from begging, and said: “The upper hand is better than the lower hand, the upper hand being the one which bestows and the lower hand which begs.” [Bukhari & Muslim]

was sitting on the pulpit and talking about charity and abstention from begging, and said: “The upper hand is better than the lower hand, the upper hand being the one which bestows and the lower hand which begs.” [Bukhari & Muslim]

We learn the following lessons from these two ahadeeth:

(a) The ahadeeth contain an exhortation to charity because the giving (upper) hand is better than the lower hand (which receives the charity). Therefore, it is better for you to be in a stronger financial position so you can spend in the way of Allah  rather than looking to others.

rather than looking to others.

(b) The best charity is to give preference to one’s family and children over others as the ahadeeth instructs us to start with those under our care.

(c) A Muslim must start with the obligatory spending due on him such as spending on his wife and children and then he may spend thereafter on whatever he wishes.

(d) The ahadeeth are also an exhortation to abstain from begging.

(e) The permissibility of seeking (halal) money so as to spend on himself and those whom he supports; then he may spend his money in the different channels of charity and righteous actions so that he may be one of the ‘upper-hand’ people.

What Do We Learn About Wealth From the Lives of the Companions?We’ve all heard stories of the lives of the early generation of Muslims and their patience during times of poverty, their zuhd (abstinence), and general avoidance of the trapping of this worldly life, but what about the rich and wealthy amongst the Sahabah, how did they live?

Khadijah  , the wife of the Prophet

, the wife of the Prophet  was amongst the wealthiest women of her time and spent a considerable amount of her fortune providing support to the Message of the Prophet

was amongst the wealthiest women of her time and spent a considerable amount of her fortune providing support to the Message of the Prophet  and to the newly emerging Muslim community in Makkah. For example, during the boycott of Muslims in Makkah, she almost single-handedly managed to get her agents to secure food and other essentials for the Muslims.3

and to the newly emerging Muslim community in Makkah. For example, during the boycott of Muslims in Makkah, she almost single-handedly managed to get her agents to secure food and other essentials for the Muslims.3

Uthman Ibn Affan  was the companion about whom the Prophet

was the companion about whom the Prophet  said: “From this day on, nothing will harm Uthman (regardless of what he does).” This was due to the fact that Uthman

said: “From this day on, nothing will harm Uthman (regardless of what he does).” This was due to the fact that Uthman  provided the resources needed for an under-equipped army that was setting out to confront the Romans who were amassing near Tabuk in the ninth year of Hijrah. Uthman

provided the resources needed for an under-equipped army that was setting out to confront the Romans who were amassing near Tabuk in the ninth year of Hijrah. Uthman  donated 300 camels, a hundred horses, and weapons on top of the thousands of dinars in money and gold4.

donated 300 camels, a hundred horses, and weapons on top of the thousands of dinars in money and gold4.

During the Caliphate of Abu Bakr  , when severe famine struck the city of Madina, Uthman

, when severe famine struck the city of Madina, Uthman  gave away an entire large caravan he received from Damascus laden with food and goods. The city’s merchants gathered at his house and offered to pay him four or five times the cost of the goods, to which Uthman

gave away an entire large caravan he received from Damascus laden with food and goods. The city’s merchants gathered at his house and offered to pay him four or five times the cost of the goods, to which Uthman  answered that he would sell his goods to the highest bidder, only to give away (for free) the entire caravan to the people of Medina for the sake of Allah

answered that he would sell his goods to the highest bidder, only to give away (for free) the entire caravan to the people of Medina for the sake of Allah  !

!

Uthman’s  complete faith in Allah

complete faith in Allah  and belief that the reward and promise of Allah

and belief that the reward and promise of Allah  is better than any worldly gain was reflected in his unparalleled generosity and eagerness to please Allah

is better than any worldly gain was reflected in his unparalleled generosity and eagerness to please Allah  by spending in the way of Allah by serving the Muslims5.

by spending in the way of Allah by serving the Muslims5.

We also learn of the great integrity and self-respect of Abdurrahman ibn Awf  : a Companion of the Prophet

: a Companion of the Prophet  who migrated to Madina penniless. When he was offered by another companion Sa’d bin Rab’I Al-Ansari

who migrated to Madina penniless. When he was offered by another companion Sa’d bin Rab’I Al-Ansari  to accept half of his property, Abdurrahman Ibn Awf

to accept half of his property, Abdurrahman Ibn Awf  graciously declined, and instead asked to be shown the way to the marketplace so he could work to earn his own living. Like Uthman

graciously declined, and instead asked to be shown the way to the marketplace so he could work to earn his own living. Like Uthman  , he too was one of the ten Companions that were promised Paradise whilst they were still alive. He also gave much in charity and would weep upon seeing the riches that Allah

, he too was one of the ten Companions that were promised Paradise whilst they were still alive. He also gave much in charity and would weep upon seeing the riches that Allah  blessed him with, remembering those of his Companions who had passed away owning little or nothing of worldly possessions6.

blessed him with, remembering those of his Companions who had passed away owning little or nothing of worldly possessions6.

We see here that Sahabah  were never attached to money and viewed money as a resource to do good, attain rewards, and as a result Allah’s

were never attached to money and viewed money as a resource to do good, attain rewards, and as a result Allah’s  Pleasure. They weren’t afraid of wealth and neither did they want to dispose of it for fear that it would ruin them because it was inherently evil, but rather they spent it in the way of Allah

Pleasure. They weren’t afraid of wealth and neither did they want to dispose of it for fear that it would ruin them because it was inherently evil, but rather they spent it in the way of Allah  and had no hesitations about working hard to earn a lawful income.

and had no hesitations about working hard to earn a lawful income.

We have seen that it is not sinful for a Muslim to wish for and desire more money, as long as his/her intentions are pure. The Prophet  stated that money is a noble possession, but only for a righteous person because the pious person will utilize his wealth properly without selfishness and greed, which deprives the wealth of Allah’s

stated that money is a noble possession, but only for a righteous person because the pious person will utilize his wealth properly without selfishness and greed, which deprives the wealth of Allah’s  Blessings.

Blessings.

The Prophet  said:

said:

“This money is green and luscious (like a ripe fruit), so whoever takes it rightfully, then what a great aid it is for him.7”

This hadith teaches us the true purpose of money, and that it can be a tool that helps us to worship Allah  . Thus seeking money (correctly) and spending (on worthy causes) will be counted as an act of worship done with the correct intention of attaining Allah’s

. Thus seeking money (correctly) and spending (on worthy causes) will be counted as an act of worship done with the correct intention of attaining Allah’s  Pleasure.

Pleasure.

The Prophet  also narrated:

also narrated:

“Once, while (the Prophet) Ayub was taking a bath naked, locusts of gold fell upon him. So he started to gather them in his clothes. His Lord called out, ‘O Ayub” Have I not given you riches?’ He replied, ‘Yes, indeed, my Lord, but I can never be self-sufficient from your blessings!”

In another narration, he responded:

“…but who is there that can be satisfied with your Mercy (so that he does not desire more)?8”

Ibn Hajar commented on this Hadith stating it is an indication of the permissibility of being eager to increase one’s (money) through halal means, but this is for the one who is confident that he will be able to thank Allah  (with the money once he obtains it). Another point of benefit is that money that is achieved through lawful (ie. halal) means has been called ‘blessings’ (barakah). Furthermore, this Hadith shows the superiority of the rich man who is thankful9.

(with the money once he obtains it). Another point of benefit is that money that is achieved through lawful (ie. halal) means has been called ‘blessings’ (barakah). Furthermore, this Hadith shows the superiority of the rich man who is thankful9.

There is no doubt that Muslims are obliged to earn their substance through permissible (halal) ways. The Prophet  said:

said:

“O people! Allah is al-Tayyib (pure), and He only accepts that which is pure! Allah has commanded the believers what He has commanded the Messengers, for He said, ‘O Messengers! Eat from the pure foods, and do right,’ and He said, ‘O you who believe! Eat from the pure and good foods We have given you.10”

Then he mentioned a traveler whose food, clothes, drink, and nourishment were all obtained through unlawful (haram) means, so how could he expect his du’a to be answered by Allah  11?

11?

Such is the obligation of earning through halal means that Muslims are encouraged to take a profession and go out to work, which is the best way to earn pure sustenance. Such is the status of halal sustenance that Islam even places manual labor in a high place! The Prophet  said:

said:

“No one has ever eaten any food that is better than eating with what his hands have earned. And indeed the Prophet of Allah, Dawud, would eat from the earnings of his hands.12”

The Prophet  was so cautious in what he ate that he would make sure that every morsel of food was halal for him to eat to the extent that it is reported that he

was so cautious in what he ate that he would make sure that every morsel of food was halal for him to eat to the extent that it is reported that he  once lost sleep due to the fear that he may have accidentally eaten a date that was not meant for him!13

once lost sleep due to the fear that he may have accidentally eaten a date that was not meant for him!13

The Companions too were very cautious about how they earned their sustenance. For example, it is reported that Abu Bakr  induced vomit after discovering that one of his servants had given him some food obtained by unlawful means.14 A similar narration is reported about Umar bin al-Khattab

induced vomit after discovering that one of his servants had given him some food obtained by unlawful means.14 A similar narration is reported about Umar bin al-Khattab  who was given milk by one of his servants and then Umar

who was given milk by one of his servants and then Umar  later discovered that the milk was taken from camels that were meant for charity.15 Another famous companion of the Prophet

later discovered that the milk was taken from camels that were meant for charity.15 Another famous companion of the Prophet  , Sa’id ibn Abi Waqqas

, Sa’id ibn Abi Waqqas  was once asked, “Why is it that your prayers are responded to, amongst all of the other Companions?” To this, he replied: “I do not raise to my mouth a morsel except that I know where it came from and where it came out of.16”

was once asked, “Why is it that your prayers are responded to, amongst all of the other Companions?” To this, he replied: “I do not raise to my mouth a morsel except that I know where it came from and where it came out of.16”

Earning through haram means causing great damage to a person’s life in this world and the hereafter. We’ve seen how the Prophet  warned that one of the consequences of haram sustenance is that one’s du’a (prayer) can be rejected by Allah

warned that one of the consequences of haram sustenance is that one’s du’a (prayer) can be rejected by Allah  . As well as this we’ve seen how the Prophet

. As well as this we’ve seen how the Prophet  and his Companions were extremely cautious in their financial dealings and strived their utmost to ensure that all of the sources of their sustenance were pure and halal.

and his Companions were extremely cautious in their financial dealings and strived their utmost to ensure that all of the sources of their sustenance were pure and halal.

The Prophet  warned us that:

warned us that:

“A time will come in which a person will not care whether what he (earned) was through halal or through haram.”

Furthermore, two of the seven deadly sins that the Prophet  warned us against involve earning through impermissible means17! Earning through haram means can also affect a person’s beliefs (aqidah) such that if a person believes that they are allowed to earn through haram means, then this is an act of disbelief as they have rejected the clear texts of the Quran and Sunnah. On the other hand, if they trivialize the sin, it can also expose the weakness of their faith (iman). Moreover, earning through impermissible means involves injustices not only to Allah

warned us against involve earning through impermissible means17! Earning through haram means can also affect a person’s beliefs (aqidah) such that if a person believes that they are allowed to earn through haram means, then this is an act of disbelief as they have rejected the clear texts of the Quran and Sunnah. On the other hand, if they trivialize the sin, it can also expose the weakness of their faith (iman). Moreover, earning through impermissible means involves injustices not only to Allah  by defying his laws and prohibitions, but it also necessitates injustices towards one’s family who will have to sustain themselves from the haram earnings of the breadwinner. This can impact Allah’s

by defying his laws and prohibitions, but it also necessitates injustices towards one’s family who will have to sustain themselves from the haram earnings of the breadwinner. This can impact Allah’s  barakah (blessings) on the family, the marital and family relationships, as well as guidance.

barakah (blessings) on the family, the marital and family relationships, as well as guidance.

Earning through haram means also involves injustices against others. Whether that is lying and cheating, taking riba, embezzling, selling intoxicants, etc., someone will always be wronged in the process for which there will be justice and retribution on the Day of Judgement – a day where the currency of trade will be good deeds and bad deeds!

Earning through haram means can also cause poverty in this world as any such earnings will be devoid of Allah’s  barakah (blessings). We are all too familiar with the depression, anxiety, and dissatisfaction of famous celebrities who are among the ‘super rich.’ Compare this to satisfied poor or middle-earning Muslims who live peaceful lives due to good health, happiness, contentment, family lives, etc.

barakah (blessings). We are all too familiar with the depression, anxiety, and dissatisfaction of famous celebrities who are among the ‘super rich.’ Compare this to satisfied poor or middle-earning Muslims who live peaceful lives due to good health, happiness, contentment, family lives, etc.

Earning your sustenance from haram ways can also incur the displeasure and wrath of Allah  as the transgressor willingly forsakes the commandments of Allah

as the transgressor willingly forsakes the commandments of Allah  in place of his/her desires. The one who truly fears Allah

in place of his/her desires. The one who truly fears Allah  and has concern for his life in the hereafter will always recognize that haram money can never purchase lasting pleasure as any punishment in the hereafter far outweighs any transient pleasure in this world.

and has concern for his life in the hereafter will always recognize that haram money can never purchase lasting pleasure as any punishment in the hereafter far outweighs any transient pleasure in this world.

Indeed, the Prophet  also warned us that one of the first questions we will be asked on the Day of Judgement is regarding our wealth; how it was earned and how it was spent.18 What response will we prepare for Allah

also warned us that one of the first questions we will be asked on the Day of Judgement is regarding our wealth; how it was earned and how it was spent.18 What response will we prepare for Allah  if we are careless about the sources of our income – something that must come before sourcing out halal meat?

if we are careless about the sources of our income – something that must come before sourcing out halal meat?

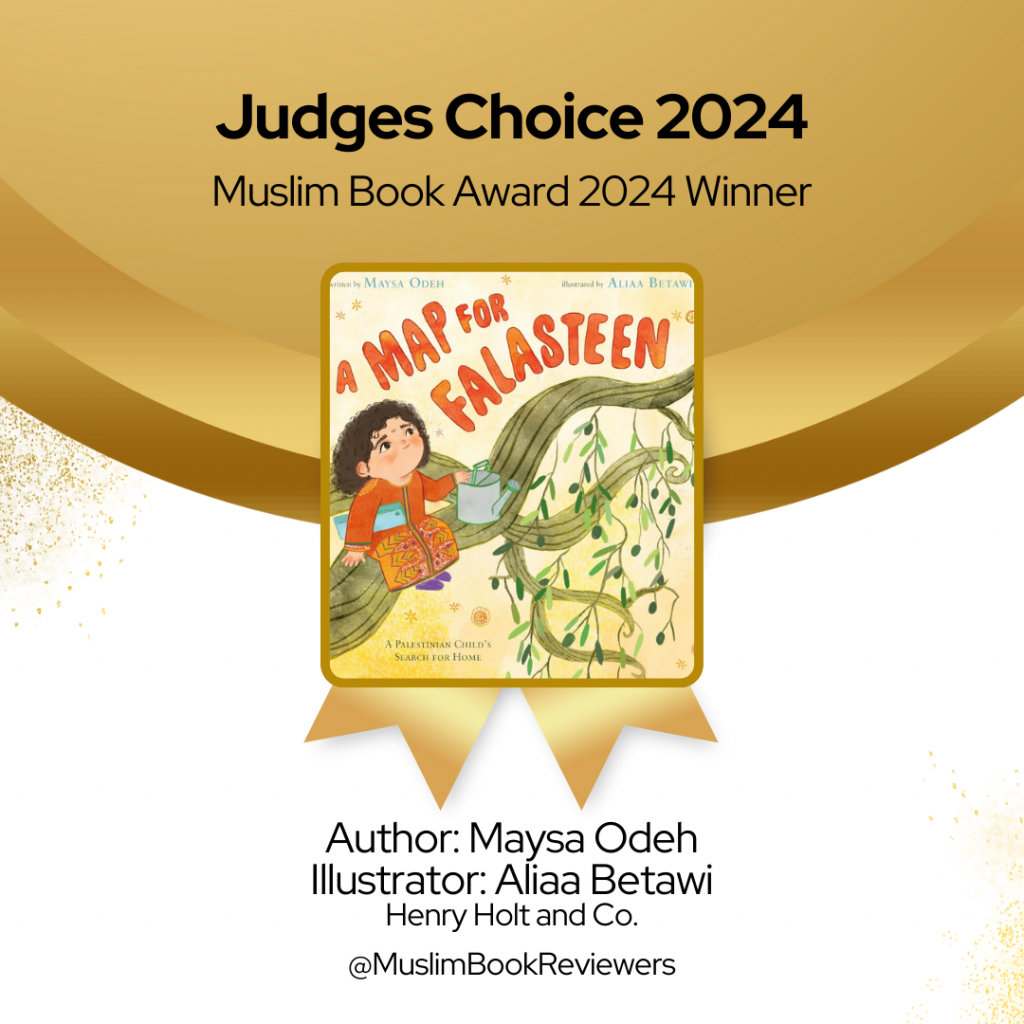

Allah [swt] asks us to seek protection from poverty. [PC: Emil Kalibradov (unsplash)]

We know that there were many poor and needy amongst the Sahabah as mentioned in the Quran19 and the ahadeeth20 of the Prophet . Those Sahabah still preferred others over themselves despite their very limited financial means. But that doesn’t mean that we should romanticize poverty or the struggles associated with it, rather poverty is one of the calamities that Allah

. Those Sahabah still preferred others over themselves despite their very limited financial means. But that doesn’t mean that we should romanticize poverty or the struggles associated with it, rather poverty is one of the calamities that Allah  may afflict people with – whether a whole society or an individual. If poverty, having little and struggling through life was the ideal situation, then the Prophet

may afflict people with – whether a whole society or an individual. If poverty, having little and struggling through life was the ideal situation, then the Prophet  wouldn’t teach us supplications to seek protection from poverty. For example, supplications such as:

wouldn’t teach us supplications to seek protection from poverty. For example, supplications such as:

“O Allah, I seek refuge in you from poverty and lack of abasement and I seek refuge in you from being oppressed and oppressing others.”21

Another supplication taught to us by the Prophet  is:

is:

“O Allah, I seek refuge in You from disbelief, poverty, and torment in the grave.”22

There is no doubt that being patient and forbearing when faced with a calamity is something that is rewarded by Allah  , but that doesn’t mean that we should be seeking to live in calamities such as poverty and struggle.

, but that doesn’t mean that we should be seeking to live in calamities such as poverty and struggle.

There is one hadith that people sometimes mistakenly use to justify or romanticize the struggle of being poor or having little, where the Prophet  said:

said:

“The poor Muslims will enter Paradise before the rich by half of a day, the length of which is five hundred years.” [Sunan Ibn Majah 4122]

However, narrations such as these do not seek to blame richness and praise poverty, rather they show that Paradise is the ultimate reward for the patience of those who were afflicted with poverty in this world. For example, the Prophet  informs us about the reward of Paradise for the mother who loses her child and is patient23, but that doesn’t indicate that suffering the loss of a child or other loved ones should be our aim; rather Paradise is the reward for patiently bearing with such difficulties.

informs us about the reward of Paradise for the mother who loses her child and is patient23, but that doesn’t indicate that suffering the loss of a child or other loved ones should be our aim; rather Paradise is the reward for patiently bearing with such difficulties.

Another reason why the Prophet  mentioned the poor entering paradise before the rich may also be because the poor will have less to account for and therefore their reckoning will be easier and shorter than the one who was blessed with a lot of halal wealth, just like a person who has multiple sources of income in this world – he will have to hire a professional accountant to do his tax returns every year, unlike the one who is employed and earns a salary from one source24.

mentioned the poor entering paradise before the rich may also be because the poor will have less to account for and therefore their reckoning will be easier and shorter than the one who was blessed with a lot of halal wealth, just like a person who has multiple sources of income in this world – he will have to hire a professional accountant to do his tax returns every year, unlike the one who is employed and earns a salary from one source24.

Now that we have established that money isn’t inherently evil, poverty is not the aim, and that Allah  actually wants us to earn our sustenance through halal means, let us now mention some of the spiritual and practical ways in which a person can increase his money and nearness to Allah

actually wants us to earn our sustenance through halal means, let us now mention some of the spiritual and practical ways in which a person can increase his money and nearness to Allah  !

!

[This is not an exhaustive list (and this article certainly doesn’t contain advice or guidance on business, commerce, or investments) and so there are many things that are beyond the scope of this article that I’ve left out.]

(1) Worship of Allah

Quite literally, turning to Allah  and prioritizing our worship will give you rizq (provision and sustenance).

and prioritizing our worship will give you rizq (provision and sustenance).

The Prophet  said:

said:

“Indeed Allah the Most High said: “Oh son of Adam, devote yourself to my worship, I will fill your chest with riches and alleviate your poverty. If you do not do so, I will cause you to become preoccupied and not alleviate your poverty.” [Jami` at-Tirmidhi 2466]

So one of the ways in which you can build your wealth and be protected from poverty is by worshipping more: fast more, pay more sadaqa, spend more time with the Quran, seek Islamic knowledge, etc.

(2) Asking Allah for forgiveness

for forgiveness

Another technique is asking Allah  for forgiveness and coming back to Him.

for forgiveness and coming back to Him.

Prophet Nuh  called his people to Allah

called his people to Allah  for 950 years. He did it publicly, he did it privately, and he did it openly using all different techniques. Nuh

for 950 years. He did it publicly, he did it privately, and he did it openly using all different techniques. Nuh  told his people:

told his people:

“Ask forgiveness of your Lord. Indeed, He is ever a Perpetual Forgiver.” [Surah Nuh; 71:10]

Nuh’s  people asked, “What do we get if we ask for forgiveness? What do we get if we turn back to Allah?”

people asked, “What do we get if we ask for forgiveness? What do we get if we turn back to Allah?”

Then Nuh  informed his people that if they turn back to Allah

informed his people that if they turn back to Allah  , He will:

, He will:

“He will send [rain from] the sky upon you in [continuing] showers…

…and give you increase in wealth and children and provide for you gardens and provide for you rivers.” [Surah Nuh; 71:11-12]

In other words, their livestock, and their agriculture would benefit from the water coming down and He would give them an increase of wealth.

Now let us pause here for a moment, if there was a contradiction between Islam and money, why would Prophet Nuh  tell the people that if they ask for forgiveness, Allah

tell the people that if they ask for forgiveness, Allah  would give them an increase in their wealth? Think about it!

would give them an increase in their wealth? Think about it!

So, in order to increase your wealth and win Allah’s  Love, ask Allah

Love, ask Allah  for forgiveness and turn back to Him.

for forgiveness and turn back to Him.

Taqwa or being conscious of Allah  is another way to gain sustenance and provision from Allah. Allah

is another way to gain sustenance and provision from Allah. Allah  says:

says:

“Whoever has taqwa of Allah, He will make a way out for them and will provide for them from a direction that they would have never imagined.” [Surah At-Talaq; 65:2-3]

So what does it mean to have taqwa of Allah  when it comes to wealth? Having taqwa in wealth means to seek a halal income and avoid jobs and positions that may compromise your Deen; avoid lying, cheating, and deception in trade, while also observing your religion in your places of work (and the list goes on).

when it comes to wealth? Having taqwa in wealth means to seek a halal income and avoid jobs and positions that may compromise your Deen; avoid lying, cheating, and deception in trade, while also observing your religion in your places of work (and the list goes on).

There are three types of charity in Islam that come under ‘spending’ in the path of Allah  . First, the two obligatory types of Zakat: zakat on one’s wealth and Zakatul-fitr (which is given at the end of Ramadan). The third type of charity is Sadaqa, which is voluntary and encouraged at every time and place. The rules of each category are found in the books of Fiqh (Islamic Jurisprudence), which is beyond the scope of this article.

. First, the two obligatory types of Zakat: zakat on one’s wealth and Zakatul-fitr (which is given at the end of Ramadan). The third type of charity is Sadaqa, which is voluntary and encouraged at every time and place. The rules of each category are found in the books of Fiqh (Islamic Jurisprudence), which is beyond the scope of this article.

The evidence from the Qur’an and Sunnah that prove that spending in the way of Allah  brings about an increase in one’s rizq are too many to mention in this article. So let us discuss a selected few.

brings about an increase in one’s rizq are too many to mention in this article. So let us discuss a selected few.

Allah  says:

says:

“Say, “Indeed, my Lord extends provision for whom He wills of His servants and restricts [it] for him. But whatever thing you spend [in His cause] – He will compensate for it; and He is the best of providers.” [Surah Sabah; 34:39]

Ibn Kathir commented on this verse to say that it means, “no matter how much you spend on matters that He had made obligatory upon you, and (on matters) that are permissible, Allah will replace it in this world with a substitute (meaning more money), and in the Hereafter with rewards, as has been explained in the Sunnah.”25

Another ayah where Allah  informs us that spending in His way will increase our wealth and sustenance is when He

informs us that spending in His way will increase our wealth and sustenance is when He  says:

says:

“Satan threatens you with poverty and orders you to immorality, while Allah promises you forgiveness from Him and bounty. And Allah is All-Encompassing and Knowing.” [Surah Al-Baqarah; 2:268]

Ibn Abbas comments on this verse and states that shaytan “promises you poverty by telling you not to spend your money! You are more in need of it and also commands you with indecent deeds. Yet Allah promises you forgiveness from these sins and sustenance by increasing your rizq.”26 Furthermore Ibn al-Qayyim states that here, “Allah  promises His servants forgiveness for his sins, and His blessings by giving him more than what he spent, many times over, either in this world, or in this world and in the Hereafter.”27

promises His servants forgiveness for his sins, and His blessings by giving him more than what he spent, many times over, either in this world, or in this world and in the Hereafter.”27

Abu Hurayrah narrates that the Prophet  said:

said:

“Allah has said: ‘O son of Adam! Spend, I will spend on you!’” [Al Bukhari]

From this very simple hadith we learn that if you spend for the sake of Allah

, He will reward you by giving you more. What a beautiful promise from Allah

– spend from whatever resources He

placed in your hands in the first place, and then He will increase it with more! How many of us truly believe and have firm faith in this promise when reaching into our pockets or bank accounts in order to give in charity for the sake of Allah

? It is for this reason that even the Prophet

also promised that charity never decreases a person’s money.28

In another hadith the Prophet  said:

said:

“There is not a day upon which the servant awakens but that two angels descend. One of them says: O Allah, repay one who spends in charity! The other says: O Allah, destroy one who withholds charity!” [Muslim]

What a great honor to have angels praying for you if you are generous in spending in Allah’s  Path and a threat to one who is stingy and miserly with his money!

Path and a threat to one who is stingy and miserly with his money!

There are ways in which you can make du’a to Allah  sincerely and ask Him for more money. Don’t just say, “Oh Allah, give me money! Give me money!” No, that’s not how you make the du’a. Rather the du’a that Allah

sincerely and ask Him for more money. Don’t just say, “Oh Allah, give me money! Give me money!” No, that’s not how you make the du’a. Rather the du’a that Allah  encourages us to make and puts on our tongue and reveals in the Qur’an is:

encourages us to make and puts on our tongue and reveals in the Qur’an is:

“But among them is he who says, “Oh Allah give us good in this world and good in the hereafter, and safety from the hellfire.” [Surah Al-Baqarah; 2:201]

So it’s not all about just focusing on the money and that’s it and it’s not all about just focusing on the hereafter and that’s it. Islam is the natural way – the solution for humanity and humans would all love to have a good life and would love to have a good hereafter so Islam brings the goodness of both worlds together.

For anybody who has a problem with wealth or whoever has a problem with money, thinking that Islam discourages it, I would ask them why

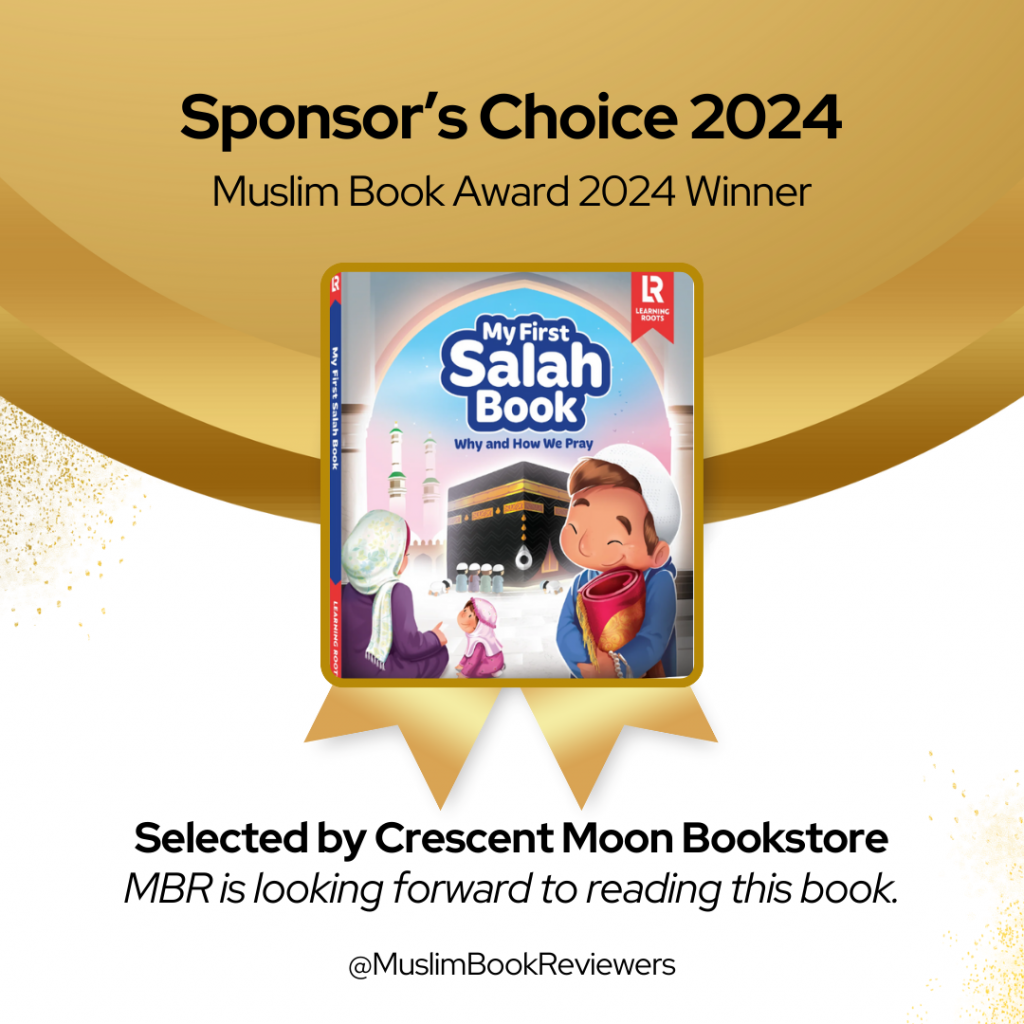

Allah encourages us to seek sustenance in this world [PC: Masjid Pogung Dalangan (unsplash)]

Allah would encourage us to ask for the goodness of this life and the goodness of the next and to seek protection from the hellfire if we were simply supposed to do with the bare minimum?

would encourage us to ask for the goodness of this life and the goodness of the next and to seek protection from the hellfire if we were simply supposed to do with the bare minimum?

Our deen encourages a middle path: to seek goodness in this life, seek goodness in the hereafter, and ask Allah  to protect us from hellfire.

to protect us from hellfire.

Putting one’s trust in Allah  means realizing that nothing happens except to the will of Allah

means realizing that nothing happens except to the will of Allah  and that everything occurs due to a Divine Wisdom. As Muslims we need to accept Allah’s

and that everything occurs due to a Divine Wisdom. As Muslims we need to accept Allah’s  Decree without questioning it or being displeased with Allah

Decree without questioning it or being displeased with Allah  – and have full faith that whatever Allah

– and have full faith that whatever Allah  has decided is from Divine Wisdom.

has decided is from Divine Wisdom.

Although tawakkul is an action of the heart, it doesn’t negate the actions of the limbs in that having true tawakkul means making every effort and doing everything humanly possible within our means to achieve a goal, and then putting one’s trust in Allah  . We all know the famous story of the Bedouin who came to the Prophet

. We all know the famous story of the Bedouin who came to the Prophet  and asked, “Should I tie my camel up (to stop it from running away), or should I have trust in Allah

and asked, “Should I tie my camel up (to stop it from running away), or should I have trust in Allah  ?” The Prophet

?” The Prophet  replied: “Tie it up, then put your trust (in Allah)!”29

replied: “Tie it up, then put your trust (in Allah)!”29

This hadith is clear proof that true tawakkul is achieved by physically striving and making an effort first to achieve a desired goal, and then having trust in Allah  .

.

Umar ibn al-Khattab  reported that the Prophet

reported that the Prophet  said:

said:

“If you were to put your trust in Allah the way that Allah deserves, then you would be provided for as the birds are: they leave (in search of food) at the beginning of the day famished, and they return at the end of the day full.”30

This hadith re-enforces the true nature of tawakkul – the bird doesn’t sit in its nest expecting that the food will come to him automatically, rather it does what many of us do to earn a living: it leaves in the early part of the day in search of food; a search which lasts the whole day only to return at dusk with a full stomach. That too, is the example of the true believer who strives in order to work and earn their sustenance, and then places their trust in Allah  .

.

Allah  also commands us in the Quran to have tawakkul:

also commands us in the Quran to have tawakkul:

“And He will provide for him from (sources) he could never have imagined. And whosever put his trust (tawakkul) in Allah, then He will suffice him. Verily, Allah will accomplish his purpose. Indeed Allah has set a measure for all things.” [Surah Al-Talaq; 65:3]

And even promises us:

“…If you fear poverty, Allah will enrich you if He wills, out of His Bounty. Surely, Allah is All-Knowing, All-Wise.” [Surah At-Tawbah; 9:28]

(7) Performing Hajj & UmrahA lot of people think about the cost, effort, and energy associated with making Hajj and Umrah, especially in our times when prices for these things have increased exponentially. However, the reality is that when a person takes the time, energy, and effort to travel for Hajj and Umrah and spends his money for the pleasure of Allah  , Allah

, Allah  rewards him by increasing his rizq.

rewards him by increasing his rizq.

Abdullah ibn Mas’ud reports that the Prophet

said:

“Follow up between Hajj and Umrah (i.e. continuously), because they both eliminate poverty and sins just like the furnace eliminates dirty impurities of iron, gold, and silver. And an accepted Hajj has no reward less than paradise.”

Here the Prophet  encouraged us to follow up one Hajj after another and one Umrah after another, which will not only remove our sins, but Allah

encouraged us to follow up one Hajj after another and one Umrah after another, which will not only remove our sins, but Allah  will also increase our rizq.

will also increase our rizq.

Another proven method for Allah  to increase your rizq is to establish the ties of kinship, which is always difficult and awkward due to trying to maintain relationships with so many people with different personalities and characteristics coupled with the family ‘politics’ that exist in every family. In fact, part and parcel of being a human is difficult family relations and that’s why the reward from Allah

to increase your rizq is to establish the ties of kinship, which is always difficult and awkward due to trying to maintain relationships with so many people with different personalities and characteristics coupled with the family ‘politics’ that exist in every family. In fact, part and parcel of being a human is difficult family relations and that’s why the reward from Allah  is great.

is great.

Establishing the ties of kinship means showing relatives kindness, compassion, and mercy, as well as paying them visits, inquiring about them, helping them, and supporting them to the best of one’s ability.

The Prophet  said:

said:

“Whoever wishes to have his rizq increased, and his life-span extended, let him establish the ties of kinship.”

(9) MarriageThis will come as a surprise to many people because the irony is that many people complain they can’t get married because they don’t have enough money, yet marriage is one of the easiest ways in which a person can guarantee an increase in his sustenance from Allah  . Allah

. Allah  says in the Quran:

says in the Quran:

“And those amongst you who are single (male and female) and (also marry) the pious of your (male) slaves and maid-servant (female slaves). If they be poor, Allah will enrich them out of His Bounty. And Allah is All-Sufficient for His creatures’ needs, All-Knowing.” [Surah An-Nur; 24:32]

There is no doubt that there is a clear difference between being responsible with your tawakkul and acting irrationally when intending to get married, but Imam Al-Sa’di in his Tafsir stated that this verse is a promise from Allah  that a married person will be enriched after being poor if he marries.31

that a married person will be enriched after being poor if he marries.31

Imam al-Qurtubi when explaining this verse also states:

“This means: let not the poverty of a man or a woman be a reason for not getting married. For in this verse is a promise to those who get married for the sake of acquiring Allah’s pleasure and seeking refuge from disobeying Him (that Allah will enrich him) … and in this verse is proof that it is allowed to marry a poor person.”32

(10) Sponsoring Students of KnowledgeOne of the noblest ways to increase one’s rizq is to financially support students of sacred Islamic knowledge so that they can be free to excel in their studies without having to worry about seeking employment in order to support themselves or their families.

The proof for this can be found in a hadith of the Prophet  where there were two brothers – one went out to work, whilst the other would come to study with the Prophet

where there were two brothers – one went out to work, whilst the other would come to study with the Prophet  . So the one who used to go out to work complained to the Prophet

. So the one who used to go out to work complained to the Prophet  about his brother, to which the Prophet

about his brother, to which the Prophet  replied: “It is possible that you are provided your rizq because of him (meaning the brother who accompanied the Prophet (saw)).”33

replied: “It is possible that you are provided your rizq because of him (meaning the brother who accompanied the Prophet (saw)).”33

Allah  promises an increase in blessings if His servants are thankful to him:

promises an increase in blessings if His servants are thankful to him:

“And (remember) when your Lord proclaimed: ‘If you are thankful, I will give you more (of My Blessings), but if you are thankless (ie disbelievers), then verily, My punishment is indeed severe.’” [Surah Ibrahim; 14:7]

For this reason, the Prophet  would always thank Allah

would always thank Allah  because it is Allah

because it is Allah  who provided for you in the first place! The true believer always thanks Allah

who provided for you in the first place! The true believer always thanks Allah  , by recognizing that all good is from Allah

, by recognizing that all good is from Allah  , praising Him and worshipping Him sincerely. Thanking Allah

, praising Him and worshipping Him sincerely. Thanking Allah  will guarantee an increase in further good and blessings from Him.

will guarantee an increase in further good and blessings from Him.

From the mannerisms of a good Muslim another way of thanking Allah  is also to thank the people who have done good for you as the Prophet

is also to thank the people who have done good for you as the Prophet  said:

said:

“He does not thank Allah, he who does not thank the People.”34

We know that Allah  is The Most-Generous and is The Bestower of Blessings, the Good-Doer (to His Slaves). The people likewise are good-doers within the limits of their ability. So whoever has good done to him by people then it is from Islamic etiquettes to thank them for being good towards him – whatever type of goodness it may be. And from the errors made is that someone does good to you and you do not thank him for his goodness nor mention him with good in order that supplication can be made for him.

is The Most-Generous and is The Bestower of Blessings, the Good-Doer (to His Slaves). The people likewise are good-doers within the limits of their ability. So whoever has good done to him by people then it is from Islamic etiquettes to thank them for being good towards him – whatever type of goodness it may be. And from the errors made is that someone does good to you and you do not thank him for his goodness nor mention him with good in order that supplication can be made for him.

The Prophet  informed us that if we wish to seek Allah’s

informed us that if we wish to seek Allah’s  Pleasure and want an increase in our rizq, then we should show kindness and mercy to the weak and destitute of our society. He

Pleasure and want an increase in our rizq, then we should show kindness and mercy to the weak and destitute of our society. He  said:

said:

“Find me amongst your weak, because the only reason that you are provided sustenance and aided in victory is because of the weak (amongst you).”

Here it is clear that Allah  will provide us sustenance and increase our rizq if we show kindness and mercy to the weak and oppressed in our society.

will provide us sustenance and increase our rizq if we show kindness and mercy to the weak and oppressed in our society.

We have seen that poverty isn’t the ideal or best way to live according to the teachings of the Quran, the Sunnah, and what we learned from the lives of the early generation of Muslims. Although we cannot say that to live the life of a rich, wealthy, and affluent person is entirely haram (as long as the source of the wealth is halal), we know that greed, miserliness, arrogance, and extravagance are also not allowed in Islam. Neither should we aim for a Muslim to eat, live, and spend only on ourselves simply to live better than everybody else. Rather it should be the aim of a Muslim to seek to earn halal wealth; to build that halal wealth and spend it on that which will bring reward and benefit to themselves, their families, and their wider Muslim community.

There were wealthy Sahabah as we have seen, but it wasn’t the money itself that led to righteousness and Paradise – it was the choices they made with it. It’s not money that can lead to Paradise or the hellfire, it depends on the choices we make with our wealth. Money doesn’t cause the situation, but our decisions; our hearts are what leads us to do good or bad. Therefore, money is a magnifier of what is in the hearts of people.

For example, we learn of Pharaoh and Qaarun in the Quran who had great amounts of wealth and we are told that they rejected the Message of Musa  . It wasn’t the wealth that ruined them, it was what they did with their wealth (i.e. mobilized their resources and army against Musa

. It wasn’t the wealth that ruined them, it was what they did with their wealth (i.e. mobilized their resources and army against Musa  ).35

).35

We have seen that wealth is both a great blessing from Allah  and a test. Money and children can be a source of comfort in this world, but it is the righteous deeds that we attain by spending that money on charitable acts and buildings institutions that will benefit our community which will remain with us permanently, and by it we can hope for Allah’s

and a test. Money and children can be a source of comfort in this world, but it is the righteous deeds that we attain by spending that money on charitable acts and buildings institutions that will benefit our community which will remain with us permanently, and by it we can hope for Allah’s  Pleasure and a permanent reward in the hereafter.

Pleasure and a permanent reward in the hereafter.

So with that in mind, if we want to seek wealth, let us seek it in a beautiful and permissible manner like the Prophet  advised36, knowing full well that surely what is in our rizq will definitely catch up with us even if we were to flee from it.37 In the end, money doesn’t make us a good person or a bad person, but it is a reflection of what is in our hearts. Let us remind ourselves of a golden rule: if we want to be rich and wealthy in order to spend for the sake of Allah

advised36, knowing full well that surely what is in our rizq will definitely catch up with us even if we were to flee from it.37 In the end, money doesn’t make us a good person or a bad person, but it is a reflection of what is in our hearts. Let us remind ourselves of a golden rule: if we want to be rich and wealthy in order to spend for the sake of Allah  , Allah

, Allah  will never bless something which He has prohibited, so always seek halal sustenance and halal means in your wealth-building journey as the Prophet

will never bless something which He has prohibited, so always seek halal sustenance and halal means in your wealth-building journey as the Prophet  summarised for us the essence of seeking Allah’s

summarised for us the essence of seeking Allah’s  Sustenance and gaining more wealth:

Sustenance and gaining more wealth:

“O Mankind. The Holy Spirit (Jibril) has whispered in my soul that no person shall die until his time is complete and his sustenance is finished. So fear Allah, and seek your sustenance in a beautiful (ie permissible manner). And let not any of you – when his sustenance appears to be delayed in arriving – try to seek it through disobeying Allah. For verily, what Allah has (with Him) can never be obtained except from obedience to Him.”38

Related:

– What Is An Imam Worth? A Living Wage At Least.

– Faith In Action: Zakat, Sadaqah, And Islam’s Role In Embracing Humanitarianism In A Globalized World

1 Umar bin Al-Khattab: His Life & Times, p. 2342 Narrated by Ibn Hibban al Mawarid (2277); Sahih as-Sirah, p. 5083 Golden Stories of Sayyida Khadijah: Mother of the Believers (Social & Economic Boycott of Banu Hashim section). 4 The Biography of Uthman ibn Affan Dhun-Nooray, p.515 The Biography of Uthman ibn Affan Dhun-Noorayn. p.716 Reported by Al-Bukhari7 Reported with various other wordings by Muslim (#6883), al-Tirmidhi (3/277) and others. 8 Reported by al-Bukhari (# 3391), al-Nasa’i (# 407) and others. 9 Fath al-Bari, v. 6, p. 48510 Reported in Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim (1015)11 Reported by Ahmed (2/328), Muslim (2/703), and al-Tirmidhi (5/220).12 Reported by al-Bukhari (2/10) and others. 13 The Prophet (saw) replied to why he could sleep all night and said: “I found a date last night under my side and ate it. Then I remembered that we had (in our house) some dates that were meant to be for charity. So I feared that the date (that I ate) was of it.” Reported by Ahmed in his Musnad (2/183 and 193).14 Al-Mishkat (# 2786)15 Al-Mishkat (# 2788)16 Shar al-Arba’in, p. 27517 The Prophet (saw) said: “Avoid the seven deadly sins (al-mubiqat): shirk, magic, killing someone without just cause, eating an orphan’s property, consuming interest, accusing chaste women of fornication and running away from the battlefield.” (Reported by al-Bukhari (5/294) and Muslim (# 89)18 Ibn Mas’ud reported: The Prophet, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “The son of Adam will not be dismissed from his Lord on the Day of Resurrection until he is questioned about five issues: his life and how he lived it, his youth and how he used it, his wealth and how he earned it and he spent it, and how he acted on his knowledge.”(Reported in Sunan al-Tirmidhi 241).19 Surah al-Hashr v. 8-9.20 A Companion of the Prophet (saw) Abu Talha welcomed a hungry traveler into his home even though they had very little to eat. Thus he asked his wife to bring whatever provisions they had and give it to the guest. As the guest ate his fill, they pretended to eat in the dim candlelight (reported in Bukhari, Muslim ,Tirmidhi, Nasa`i)21 Sunnan Abi Dawud 1544 (Book 8, Hadith No. 129).22 An-Nasa’I 147 (graded Hasan)23 The Prophet (saw): “any woman who loses three of her children, they will be a shield for her against the Fire.” A woman asked “and two?” He (saw) said, “even two.” Narrated by al Bukhari (99) and Muslim (1486). 24 Dr Qadhi ‘15 Ways to Increase Your Earnings From the Qur’an and Sunnah,’ (Hidaayah Publications, 2002m p. 33).25 Tafsir Ibn Kathir (3/595)26 Reported in al-Tabari (5/571)27 Tafsir al-Qayyim, p. 16828 Abu Huraira reported: The Messenger of Allah, peace and blessings be upon him, said, “Charity does not decrease wealth, no one forgives another but that Allah increases his honor, and no one humbles himself for the sake of Allah but that Allah raises his status.” (Reported in Sahih Muslim, 2588)29 Reported by Ibn Hibban in his Sahih (# 731 of the Ihsan edition), and al-Hakim in his Mustadrak (3/623).30 Reported by al-Tirmidhi in his Sunnan (# 2447), Ibn Majah (# 4216), Ahmed in his Musnad (# 205), Ibn Hibban in his Sahih (# 559 of the edited Ihsan), al-Hakim in his Mustadrak (4/318), and others. 31 Tafsir al-Sa’di, p. 516. 32 Tafsir al-Qurtubi, v. 12, p. 220. 33 Sunan Al-Tirmidhi (#2448), al Haakim (1/93). 34 Reported by Abu Dawud (# 4811), At-Tirmidhi(# 1954), Ahmad (# 7939)35 Surah al-Ankabut verses 29 & 39 and al-Qasas verses 28 & 76-8236 The Prophet (saw) said: “Seek this world in a beautiful manner, for every person’s affairs have been made easy for him, according to what he has been created for.” (Reported by Ibn Majah (2/3).37 The Prophet (saw) said: “Of the son of Adam were to flee from his rizq the way that he flees from death, then of a surety his rizq would catch him just as death does.” (Reported by Abu Nu’aym in his Hilya (7/90 and others).38 Reported by Al-Hakim (2/4) who declared it authentic, and al-Dhahabi agreed with him; Ibn Hibban (# 1084 of the Ihsan edition); and al-Baghawi in his Sharh al-Sunnah, and it is recorded in al-Mishkat (# 5300).The post Money And Wealth In Islam : The Root Of All Evil? appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.