Swiss federal court rules in favor of Ali Abunimah

Ban lacked evidence that journalist’s speech violated the law or that he posed any threat to Switzerland.

Ban lacked evidence that journalist’s speech violated the law or that he posed any threat to Switzerland.

Two Palestinian men shot and killed by rampaging settlers in occupied West Bank.

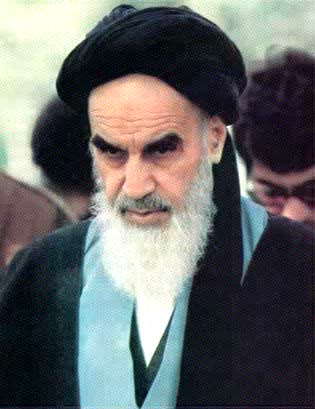

The assassination of Iran’s long-ruling leader, Ali Khamenei, at the outset of another treacherous Israeli-incited American attack at the end of winter 2026 casts a long shadow. Not only are prospects of resolution incalculably damaged, but Khamenei’s killing marked the end of one of the most paradoxical and polarizing figures in contemporary history, one who had overseen a paradoxical hybrid parliamentary regime in Iran that yet entrenched a clerical-military nexus at whose apex he stood for nearly fifty years.

A Revolutionary BackgroundVilified by Iran’s many enemies, certainly his killers, as a “fanatic” or “tyrant”, Khamenei was also seen by large swathes of the world, including but not exclusively Shias, as a “martyr”, not least for the circumstances in which he was treacherously cut down. Still lucid in his eighties, he defied easy categorization: a vastly read intellectual and a youth activist, he was nonetheless quick to resort to bloody repression at the helm of what was essentially a religious-cum-military clique in power; a proponent of internationalist solidarity, he was nonetheless comfortable with adopting narrow Iranian statism when it suited him; a repeated claimant of cross-sectarian solidarity among Muslims, he oversaw policies that repeatedly pushed other Muslims under the bus; a sharp critic of Western imperialism and advocate of Muslim independence, he proved nonetheless willing to join in imperial misadventures even if at arms’ length, yet was cut down by the same misadventures. What is certain is that Khamenei’s killers, the genocidal Israeli ethnostate and its enablers, and the circumstances in which he was slain were worse than the man.

“In the late 1970s, Rouhollah Khomeini was the spearhead of a mass revolt that forced out the monarchy into exile.”

More than anything, Khamenei epitomized the limitations of the revolutionary intellectual as ruler; he was without question a widespread multilingual reader, and engaged over the years with works as varied as those of Malcolm “X” Shabazz, Muhammad Iqbal, Sayed Qutub, Victor Hugo, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Leo Tolstoy. What most of these writers had in common was criticism of the status quo, something that no doubt appealed to a man who had grown up in an Azeri family under a tightly repressive monarchy led by the Pahlavi family. One of Khamenei’s influences was Navab Safavi, an Islamist ideologue who had assassinated the pro-British military prime minister Ali Razmara in 1951. Another prime minister, Hassan Mansour, fell prey to a similarly motivated assassination in 1965. In between, when Khamenei was just a teenager in 1953, the United States and Britain helped the monarchy oust an elected government for blatantly material interests related to Iranian oil.

The Pahlavi regime that lasted until 1979 was not only a monarchy, nor just a Western vassal, nor simply an elitist regime with open and often unconcealed racial disdain for outsiders, but one of the most brutal police states of the day, whose repression comfortably dwarfed that of the regime Khamenei himself would lead. He was repeatedly jailed in his prime years, a period when monarchic repression duelled with underground resistance of various types – Muslim, leftist, liberal, ethnic, and other. The most recognizable opposition leader was Rouhollah Khomeini, a firebrand preacher under whom Khamenei had studied. In the late 1970s, Khomeini was the spearhead of a mass revolt that forced out the monarchy into exile, where its loyalists have since constituted a nostalgic, myopic, and obnoxious segment of the Iranian diaspora.

Revolution, War, and ConsolidationAt home, however, the revolution narrowed to a smaller circle. At first expected to be more of a symbolic ruler alongside a prime ministry and presidency, Khomeini became the increasingly powerful leader of a circle increasingly comprising men of his background: clerics, almost invariably Shia clerics, in what was called Vilayet-e-Faqih, or the State of the Jurists. This was Khomeini’s preferred innovation and underpinned the hybrid nature of the regime: while it held regular elections for the presidency and elected officials wielded significant local control, their decisions were subject to largely clerical review while executive power rested with a clerical “supreme leader”.

Around Khomeini were gathered fellow clerics as well as revolutionary activists and military officers: either officers who had been dissidents under the monarchy or revolutionaries-turned-generals during the 1980s Gulf war with Iraq. Indeed, Khamenei’s principal interest in the revolution’s immediate aftermath seems to have been in forming a military and security network: over the war’s years, this would expand into a vast praetorian corps called Pasdaran, or Islamic Revolutionary Guards. He often visited the battlefield and worked closely with rising military stars such as Mohsen Rezai, Bagher Ghalibaf, and – perhaps best-known outside Iran – Ghassem Soleimani.

Their power increased amid crackdowns on rival revolutionaries as well as American-backed monarchists. Similarly, they were strengthened by the 1980s Gulf War. The fact that Iraq, whose dictator Saddam Hussein had formally taken over just after the Iranian revolution, invaded meant that, like its monarchic predecessor, Khomeini’s regime could rally on nationalist sentiment, if with a more religious tenor than before. Iran largely relied on mass attacks – where thousands of fighters might be slain at a time – to offset the Iraqi technological advantage, and this required motivation of the type that clerical warriors like Khamenei could give. Although Tehran formally disavowed sectarianism – cultivating certain Sunni allies abroad and formally reining in some sectarian rhetoric at home – the narrative could also take on sectarian tones, especially with regard to the Gulf, whose rulers were pro-West as a rule and had largely backed Iraq through well-grounded fears of Iranian subversion.

Paroxysms and PromotionsEven as the war raged, in summer 1981, a series of paroxysms struck Iranian politics. These were largely related to the Mojahedin-e Khalgh, a network led by the Rajavi spouses Massoud and Maryam that competed with Khomeini. Though they had played a major role in the 1979 revolution with a mixture of Muslim and Marxist rhetoric, the Rajavis had been frozen out since, and joined Iraq’s side; the rather cultish and freely murderous nature of their organization made them an easy target against which the regime could rally.

Khamenei himself was badly injured and lost the use of an arm when a Khalgh assassin tried to kill him. Only days earlier, the parliament, led by a frequent ally of Khamenei, Akbar Hashmi-Rafsanjani, had impeached the increasingly weak incumbent of the presidency, Abolhassan Banisadr, who was accused of being soft on Khalgh and fled abroad. After a snap election, Banisadr’s prime minister, Mohammad Rajai, replaced him, only to be assassinated along with his own prime minister, Javad Bahonar, by Khalgh before the summer was out. In these circumstances, Khamenei, still only recently recovered from injury, won the election of autumn 1981 to take over the presidency, with Mir-Hossein Mousavi as prime minister. In contrast to Banisadr, Khamenei was fiercely loyal to Khomeini’s policy, and this was a major step in the entrenchment of their clique.

Ali Khamenei served as Iran’s president from 1981 until 1989 [PC: Getty Images]

Foreign observers of Iranian politics often divide camps into “moderates” and “hardliners”, but this is a major oversimplification that overlooks how political camps actually functioned. Khamenei would adopt conciliatory policies at some junctures and uncompromising ones at others: what he prized was the maintenance of an order that he deemed necessary for the “revolutionary” regime’s survival.One example came when, in 1982, the Iranians spectacularly expelled the Iraqi army. Fearful of Iranian expansion, Saudi Arabia, which generally supported Iraq, offered reparations and conciliation. In the ensuing debate, it was the “hardliner” Khamenei who favoured taking the Saudi deal in order to focus on consolidation; by contrast, Prime Minister Mousavi and Khomeini’s deputy Hossein Montazeri, often seen as “moderates”, favoured “spreading the revolution” by attacking Iraq. Khomeini agreed; for once, Khamenei was overruled, and Iran proceeded to attack Iraq that summer; though Iranian propaganda frequently described the 1980s Gulf War as an “Imposed War” because of Iraq’s initial attack, in fact, most of the remaining six years would see Iran attacking its hitherto beaten neighbour.

Also defying easy definitions, Iran supported Syria’s regime, which brutally crushed an Islamic revolt but shared Iran’s enemy in Iraq. In the Lebanese war, Iran’s beneficiaries, which eventually became known as Hezbollah, fought against both Syrian and Israeli proxies; yet Iran and Israel also shared an enemy in Iraq, which was by the mid-1980s formally backed by the pro-American Gulf states. Even as they were fighting over Lebanon, Iran and Israel secretly cooperated against Iraq in weapons transfers in which neoconservative officials from the American government were also involved. Thus, the Americans found themselves backing both sides in the Gulf: they openly backed Iraq, and even attacked Iranian ships, but also secretly armed Iran.

The 1980s Gulf War ended with the Iraqi reconquest of the peninsula and a failed Khalgh incursion into Iran, after which the Iranian regime mounted a series of mass crackdowns and executions. This outraged deputy ruler Montazeri, who was quickly replaced with the less squeamish Khamenei just months before Khomeini (1979-89) passed away. Khamenei replaced him, and the regime was reorganized to institutionalize his power; the prime ministry, held by Mousavi, was abolished, and the Iranian “Supreme Leader” could rule for life. This position was loosely akin to that of a constitutional monarch, albeit one that had far more active engagement with its establishment than most contemporary monarchs. Hashmi-Rafsanjani, who now took the still-electable presidency, claimed that Khamenei felt suffocated by the new responsibility, but if this was so, Iran’s new ruler certainly didn’t let such feelings interrupt a decades-long rule.

Rhetoric versus Practice: Mixed Relations with the United StatesIn his new role as paramount leader, Khamenei adopted a position of dignified aloofness from the rough-and-tumble of day-to-day politics and party bickering, but reserved the privilege to occasionally comment if he felt things were going too far. The Iranian regime, by the 1990s, had adopted a longer-term entrenchment, though the political arena was still primarily contestable by either veterans of the early revolution or by allied clergy and technocrats. This led to something of an unofficial oligarchy, with rotating figures emerging as fixtures in the political elite; the fabulously wealthy Hashmi-Rafsanjani, by no means a bloodcurdling revolutionary, was often a favoured target of criticism.

But Khamenei was still flexible enough to work with politicians whose platforms he disapproved, perhaps in part because they shared his social background. Hassan Rouhani, like Khamenei, a cleric with close military links, chaired the security council for years despite a well-known openness to dealing with the West. In 1997, Mohammad Khatami, an openly pro-Western cleric who urged political change, won the election and, despite frequent grumbling from Khamenei and the generals, lasted two successive terms in the presidency.

The Iranian regime had long complained about “Gharbzadegi” or “Westoxification” – the inclination to be culturally awestruck by Western material advantages – but this did not extend to occasional collaboration. In fact, Khamenei and his generals, who still held the whip hand on foreign policy, were less averse to cooperation with the West than rhetoric suggested. A case in point was the 2001 American invasion of Afghanistan, which Iran enthusiastically supported to oust a Taliban regime that Khamenei had castigated as upstarts.

This was doubly the case when, in 2003, the Americans invaded Iraq. Though the neoconservative-dominated American regime had made no secret of its ambitions to soon attack Iran, the prospect of finally ousting Saddam and tapping into Iraq was one that Khamenei could not resist, especially given Iran’s years-long influence with a large number of Iraqi opposition groups, largely though not exclusively Shia exiles. When one such exile oppositionist, the commander Jamal Jafar (Abu Mahdi), objected to working with the Americans, Khamenei personally overruled him in the interest of ousting the Iraqi Baath regime. It was not until their mutual enemy was defeated and Iraq conquered that the United States and Iran resumed their rivalry, with Iran backing militants against the Americans’ British confederates. Yet even in Iraq, they often competed over the same clientele, including Iraqi Kurdish militias and also Jawad Maliki, who was at first promoted in 2006 by the United States, but backed by both Iranian and American support in consolidating his power.

Resistance and Its LimitsOne frequent American accusation, first planted and endlessly rehashed by Israel, was that Iran was on the verge of obtaining nuclear weapons, supposedly to annihilate Jews. This was bloodthirsty fantasism for a number of reasons, not least that Khomeini had always opposed nuclear weapons and Khamenei repeatedly abandoned opportunities to cultivate them, for example, with a Pakistani offer of enrichment. In the period of American-Israeli aggression, this failure to adopt a deterrent looks increasingly naive.

Instead, Iran focused on cultivating a network of mostly militia allies in the region, and largely limited alliances with American rivals like Russia. These were grandly dubbed an “Axis of Resistance”, appropriating an American propaganda term that had placed Iran in an “Axis of Evil”. Like the American term, this term itself was largely misleading; in such countries as Iraq, the “Axis of Resistance” chronically cooperated with the same Americans whose empire it was meant to be resisting. It also frequently belied Iranian rhetoric; while Iran had long distanced itself from sectarianism, it frequently relied on thuggish sectarian confederates in Iraq and Syria.

Nonetheless, the United States and especially Israel remained hostile to Iran. One favourite target was Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the voluble populist who replaced Khatami in the presidency. At first, Khamenei backed Ahmadinejad, notably in a 2009 reelection over the 1980s prime minister, Mousavi. Now an opposition figure calling for reform, Mousavi was put under house arrest and the protests in his favour were crushed. However, Ahmadinejad’s populism frequently clashed with the interests and views of Khamenei’s own establishmentarian clerical and military-security networks, and the pair frequently diverged over the ensuing years.

In 2013, Ahmadinejad was replaced with a more familiar figure: unlike the populist, Rouhani was an establishment man, a soldier-cleric like Khamenei himself; also unlike Ahmadinejad, he was eager to reach an accord with the United States, based on shared interests in Syria and Iraq. In Iraq, Maliki’s regime – backed by both the United States and Iran – faced a revolt quickly dominated by the millenarian Daesh organization; in Syria, an Iran-backed regime faced both Daesh as well as a revolt backed by Turkiye. Iran invaded Syria in 2013, and the United States in 2014. In Iraq, both cooperated against Daesh. Ghassem Soleimani rallied such Iraqi lieutenants as Jamal Jafar to hold their noses and cooperate with the American military against an Iraqi rival, as they had done in 2003. This helped facilitate a short-lived deal between the United States and Iran over nuclear enrichment, over voluble Israeli protests, at Vienna in 2015. Khamenei had given Rouhani a long leash for diplomacy with the United States, but his misgivings about this approach were vindicated when, in 2017, the more aggressive American regime of Donald Trump abruptly scrapped the agreement.

With failed diplomacy toward Washington came destructive wars in Iraq and Syria. The cost of these campaigns was enormous; tens of thousands had been killed, and Iran’s particular intervention in Syria in the service of a vicious and fickle dictatorship would come to naught; the Assad family would indeed betray and abandon the “Axis of Resistance” even before their own ouster in 2024, and the fact that Israel immediately attacked their Turkish-backed foes underlined the hollowness of Iran’s claim that the Assad family would be a bulwark against Israel. As with the original support for the 2001 Afghanistan invasion and 2003 Iraq invasion, diverting so many resources for undisguisedly vicious and unprincipled regimes was a policy that Khamenei would have cause to regret.

Confrontation

“With Daesh out for the count, America and Iran again diverged, and in 2020, Trump had Ghassem Soleimani and Jamal Jafar assassinated in a standoff in Iraq.”

With Daesh out for the count, America and Iran again diverged, and in 2020, Trump had Ghassem Soleimani and Jamal Jafar assassinated in a standoff in Iraq. An outraged Khamenei’s threats were not matched by repeatedly faltering Iranian reciprocations. Similarly, there was no meaningful Iranian response when, in 2023, the Palestinian Hamas in Gaza, to which Iran was only loosely attached, broke out of a decades-long siege and seized hostages in a bloody raid before a genocidal Israeli assault over the region. Though Israel insisted on treating Hamas as an Iranian proxy, Tehran took care to avoid meaningful confrontation. This continued right until the summer of 2025, when a reinstalled Trump helped Israel attack Iran, in the process wiping out a wide swathe of leaders with whom Khamenei had worked for decades.

Nor were external attacks the only front. Over the 2020s, Iran was beset by internal protests, which contained both organic elements but also, as in the most recent case, disruptive elements clearly linked to Israel. As in the past, Iran resorted to violent repression, whose scale was instantly, shamelessly, and absurdly exaggerated by its enemies. Their most ludicrous yet frequently mulled claimant to replace the clerical regime was the posturing, utterly incompetent heir to the Pahlavi name, Reza Shah, who had grown up in an American exile, was leery of resettling in Iran, and had no credentials for the job beyond his surname and a particularly shameless courtship with Israel.

Given these multivariable threats and a clear track record of the United States and Israel breaking their agreements, it seems incredible that Iran once more resorted to the negotiating table. Clearly, Khamenei’s long-articulated suspicions of the American-Israeli axis had no veto on the matter. It came as no surprise when, at the end of February 2026, with negotiations still underway, another American-Israeli barrage hurtled into Iran. On their occasion, they got Khamenei; perhaps resigned to a revolutionary end, the elderly Iranian leader was reportedly sitting with an infant granddaughter when both were killed.

Khamenei is the latest, but most powerful, of a line of leaders to have been assassinated by the United States and Israel – among others, Yemeni, Palestinian, and Lebanese leaders. But owing in part to his longevity at the helm of an at least independent, if not always, anti-imperial regime; in part to his position as the seniormost Shia politician in the world; and in part to the dishonourable methods of the genocidal enemy that had killed him, Khamenei’s death has already provoked more international outcry than most. The tragedy is not, as his killers’ propaganda has it, that he ran a supposedly millennarian regime bent on regional conquest. The tragedy is that his revolutionary-philosophical background, decades in near-unchallenged power, and proven ability to retain his position, did not equip him to adequately confront his country’s open enemies. He recognized them far better than many other rulers in the region, but his policies, from abjuring nuclear armament to the cultivation of divisive vassals in the Fertile Crescent, did little by way of that recognition and ensured that the revolutionary republic to which he dedicated his career is in as parlous a state at his demise as it has ever been.

[Disclaimer: this article reflects the views of the author, and not necessarily those of MuslimMatters; a non-profit organization that welcomes editorials with diverse political perspectives.]

Related:

– Iranian Leader Khamenei Slain As War Brings Mayhem To The Gulf

– Genocidal Israel Escalates With Assault On Iran

The post Revolutionary Philosopher And Potentate: The Life And Polarizing Legacy Of Ali Khamenei appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

This series is a collaboration between Dr. Ali and MuslimMatters, bringing Quranic wisdom to the questions Muslim families are navigating.

When Your Teen is DepressedThere is a conversation happening in Muslim homes across the East and West right now that is costing lives.

It goes something like this: A teen is struggling. Not just spiritually dry, not just going through a rough patch — genuinely struggling. Withdrawn. Sleeping too much or not at all. Unable to feel enjoyment in anything. Sometimes expressing hopelessness. Sometimes thinking about not being here anymore.

And the response from the community, from extended family, sometimes from parents themselves, is some version of: “They just need more iman. More prayer. More Quran. A stronger connection to Allah.”

This response is not evil. It comes from a real belief that spiritual health and mental health are intertwined — which is partially true. It comes from love, from wanting to help, from a tradition that does teach that the heart is the center of wellbeing.

But in the case of clinical depression, this response can be catastrophic. It delays treatment. It adds shame to suffering. It can make a struggling teen feel that their illness is a moral failure. This only deepens the illness and can sometimes lead them to just give up on everything; sometimes even life.

This piece is for the parent who wants to do better.

First: Understand what depression actually isDepression is not sadness. Sadness is a normal human emotion that comes and goes in response to circumstances. Depression is a medical condition involving measurable neurological changes — dysregulation of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, structural changes in the hippocampus, altered prefrontal cortex function — that persist regardless of circumstances and significantly impair a person’s ability to function.

A teen with clinical depression is not choosing to feel bad. They are not failing to try hard enough. Their brain is malfunctioning in a specific, documented, treatable way.

The criteria we use in medicine to diagnose a major depressive episode include five or more of the following, present for at least two weeks:

This is not a spiritual condition. It is a medical one, and it requires medical attention.

Why are we hearing more about mental illness these days?

While mental illness has existed throughout all of human history, it does statistically appear to have increased in a dramatic way over the past few decades. While a detailed exploration for the reasons behind this are beyond the scope of this article, I would like to reflect briefly on one of these reasons: stress.

One of the recurring themes of this series has been an attempt to help parents understand just how stressful the lives of their kids are today. While this stress is possibly worse in the west, it is quickly becoming a global crisis with the spread and penetration of social media and internet.

Your kids are going through intense pressure trying to fit in to a culture and system that is almost entirely the opposite of Islam. This is not only a problem Muslim kids face, but increasingly a problem being voiced by kids of other faiths too. We live in a godless society that prioritizes following your whims and pleasures, and it can quite literally break the psyche of your child.

What the Prophet ﷺ taught about illness and treatmentThe Islamic tradition is not anti-medicine. It is explicitly pro-medicine.

The Prophet ﷺ said: “Make use of medical treatment, for Allah has not made a disease without appointing a cure for it.” (Abu Dawud — sahih)

He also said: “There is no disease that Allah has created, except that He also has created its cure.” (Bukhari)

These are not metaphorical statements about spiritual remedies. They are instructions to seek treatment. The Prophet ﷺ himself used and recommended physical remedies for physical illness, enough that there is a science called “at-Tibb an-Nabawi” (The Medicine of the Prophet). The principle extends naturally to mental illness, which is, at its root, a physical illness of the brain.

A Muslim parent who prevents their depressed child from accessing mental health treatment — on the grounds that therapy is un-Islamic or that the child just needs more prayer — is acting against the Sunnah. This is a hard thing to say, but it is true, and families need to hear it.

I do understand where this resistance comes from to an extent. Western, or secular, psychiatry has been associated with atheism and has often demonstrated a negative view of religion and religious ideas. And so it does make sense that a Muslim would not want a Muslim loved one to go to such a person for fear that they would turn them away from Islam in their vulnerable condition.

But, subhan Allah, our community is filled with Muslim psychiatrists and therapists. Many of these people are among the most compassionate, kind and devout people I have met, alhamdulillah.

They have an impressive record of helping Muslims struggling with mental illness, and have an equally impressive record of helping them without the need for medication. As a doctor who treats mental illness as part of my own family practice, I try very hard, with all my patients, to limit the use of medication unless it is absolutely necessary and the benefits outweigh the risks.

Prophet Ayyub and the theology of sufferingThe story of Ayyub ﷺ is the Quran’s most extended treatment of prolonged suffering. And it teaches something that directly contradicts the “depression equals weak faith” narrative.

Ayyub ﷺ was a prophet — among the most righteous of human beings. And he suffered. For a very long time. With illness, loss, and social isolation that any clinician today would recognize as a major risk factor for severe depression.

Allah does not describe this as punishment for weak faith. He describes Ayyub as sabbar — deeply patient — and awwab — constantly returning to Allah. [38:44]

The Quran does not say Ayyub suffered because he lacked iman. It says he suffered because he was being tested. And it says Allah responded to his cry — not after he performed perfectly, not after he stopped feeling pain, but when he brought his raw suffering directly: “Hardship has touched me.” [21:83]

If a prophet of Allah could suffer in ways that resemble clinical depression — if Allah tested him that way, called him righteous through it, and answered his cry from within it — then the framework that equates suffering with spiritual failure has no Islamic foundation.

Your teen’s depression is not evidence of their moral failure. It may be, in ways we cannot fully see, a test. What matters is that they get the support needed to get through it.

The critical distinction: spiritual struggle vs. clinical depressionThese two conditions overlap and interact — but they are not the same, and equating them causes harm.

Spiritual struggle typically presents as: feeling distant from Allah, loss of motivation for ibadah, questioning faith, feeling like prayer is hollow. It often responds to: increased dhikr, scholarly guidance, community connection, addressing specific sins or patterns, and simply time and patience. The person still experiences pleasure in other areas of life. Their basic functioning is largely intact.

Clinical depression typically presents as: pervasive low mood lasting weeks, inability to feel pleasure in anything — not just ibadah — changes in sleep, appetite, and energy, cognitive impairment, and in serious cases, thoughts of death or self-harm. While spiritual practices can help, it does not reliably respond to increased religious practice alone. It requires professional evaluation and often clinical treatment.

The important nuance: spiritual neglect can worsen depression. A teen who is also cut off from Allah, from community, from prayer, has fewer internal resources and less hope. Spiritual health is not irrelevant to mental health. But it is not the cause of clinical depression, and prayer alone is not a sufficient treatment for it.

The wisest approach holds both: address the spiritual dimension and ensure the teen receives appropriate clinical care.

Warning signs that require immediate professional attention

Parents should treat the following as urgent:

Any expression of suicidal ideation — including passive expressions like “I wish I wasn’t here,” “everyone would be better off without me,” or “I don’t see the point of going on.” Take these seriously every time. Do not wait to see if they pass.

Self-harm — including cutting, burning, or other methods of inflicting physical pain. This requires professional evaluation immediately.

Psychotic symptoms — hearing voices, seeing things others don’t see, severely disorganized thinking. This requires emergency psychiatric evaluation.

Significant functional decline — unable to attend school, eat regularly, maintain basic hygiene — for more than a few weeks.

If any of these are present, the first call is to a medical professional, not an imam. Both may eventually be needed — but medical safety comes first.

What to say — and what not to say

Don’t say:

Do say:

How to find Muslim-informed mental health support

Not every therapist is equipped to work with Muslim teens. Cultural and religious competence matters. Look for:

Khalil Center (khalilcenter.com) — one of the most established Muslim mental health organizations in North America. Integrates Islamic spiritual care with evidence-based clinical practice. Telehealth available.

Noor Human Consulting — Muslim therapists and counselors with an explicit Islamic framework.

Your child’s school counselor or pediatrician — as a first point of contact and referral. A good referral to a culturally sensitive therapist is better than no help at all.

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline — if your teen is in crisis, call or text 988. This is a 24/7 resource.

When speaking with a therapist, it is entirely appropriate to ask: “Do you have experience working with Muslim patients?” and “Are you comfortable with my child’s faith being part of our conversations?”

A word about medication

Some parents resist the idea of psychiatric medication on religious grounds, believing it alters the mind Allah created. This concern deserves a serious response.

The brain is an organ. When the brain’s chemistry is disrupted by illness, restoring that chemistry through medication is not tampering with Allah’s creation — it is treating illness, exactly as the Prophet ﷺ instructed. Insulin for a diabetic, antibiotics for an infection, antidepressants for a brain condition that is causing suffering and impairing function — these are all in the same category.

The decision about medication should be made in consultation with a qualified psychiatrist or physician, weighing the severity of the condition, the specific risks and benefits, and the patient’s overall situation. It is a medical decision, not a theological one.

And, as stated above, medicine is not needed in all cases, and is not necessarily needed for life when started.

Discussion questions for families

For teens:

For parents:

For discussion together:

What is the difference between having weak faith and having an illness?

The bottom line

Your teen’s depression is not a sign that you failed as a Muslim parent. It is not a sign that they have failed as a Muslim. It is an illness that requires treatment — clinical, spiritual, and relational.

Ayyub ﷺ suffered. Allah answered. And the answer came not by telling him his faith was weak, but by responding to his honest cry.

Be the person in your teen’s life who makes it safe to cry out.

Continue the Journey

This is Night 17 of Dr. Ali’s 30-part Ramadan series, “30 Nights with the Quran: Stories for the Seeking Soul.”

Tomorrow, insha Allah: Night 18 — When Bad Things Happen to Good People (and: Is it okay to be angry at Allah?)

For daily extended reflections with journaling prompts, personal stories, and deeper resources, join Dr. Ali’s email community: https://30nightswithquran.beehiiv.com/

Related:

I Can’t Feel Anything in Prayer – Understanding Spiritual Dryness | Night 16 with the Qur’an

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

The post Is Depression a Lack of Faith? A Guide for Muslim Parents | Night 17 with the Qur’an appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Some people enter Ramadan with excitement, surrounded by community, family, and familiar rituals. Others enter it carrying fractures — the kind life leaves behind when responsibilities are heavy, relationships are strained, or the heart has been quietly breaking for far too long.

For many believers, Ramadan does not enter a life that is whole. It arrives into exhaustion. Into loneliness. Into grief that has been waiting for a place to land. Into a heart that has been whispering, “Ya Allah, I don’t know how much more I can hold.”

And yet… Allah  chooses this month as a mercy.

chooses this month as a mercy.

In the Qur’an, He tells us:

“Allah intends for you ease, and He does not intend for you hardship.” [Surah Al-Baqarah; 2:185]

This verse is not simply about fasting — it is about the nature of Ramadan itself. Ramadan is ease wrapped in discipline. Healing wrapped in worship. A divine pause in the middle of a life that often feels relentless.

Because Ramadan does not ask you to be whole before you enter it. It asks you to show up — even if you are limping.

Ramadan Heals in Ways People CannotThere are wounds people don’t see. There are burdens you carry quietly because you don’t want to be a source of worry. There are disappointments you’ve swallowed so many times that you’ve forgotten what it feels like to breathe without tension.

Ramadan meets you there.

When you wake up for suhoor half-asleep and weary, Allah  sees it. When you drag your tired body to pray, even with a heart that feels numb, Allah

sees it. When you drag your tired body to pray, even with a heart that feels numb, Allah  counts it. When you whisper du‘ā’ with a voice that trembles, the angels lift it.

counts it. When you whisper du‘ā’ with a voice that trembles, the angels lift it.

Ramadan is not a month of perfection — it is a month of return.

The Qur’an as a Medicine for the Fractured HeartAllah  calls the Qur’an:

calls the Qur’an:

“O mankind, there has to come to you instruction from your Lord and healing for what is in the breasts and guidance and mercy for the believers.” [Surah Yunus; 10:57]

Not a healing for the body. Not a healing for circumstances. A healing for the heart — the place where disappointment, fear, and longing live.

This is why Ramadan feels different. It is the month where the Qur’an descends again into the cracks of your life, filling them with light you didn’t know you still had access to. This happens not magically, but through action: reciting the Quran in salat and out of it, learning it, and putting it into practice.

The Du‘ā’ of the Broken but BelievingThere is a du‘ā’ that belongs to those who feel overwhelmed, stretched thin, or quietly hurting:

“And [mention] Zechariah, when he called to his Lord, ‘My Lord, do not leave me childless, while you are the best of inheritors.” [Surah Al-Anbiya; 21:89]

It is the du‘ā’ of a prophet who felt isolated. It is the du‘ā’ of someone who had lost almost everything. It is the du‘ā’ of someone who still believed Allah  would answer.

would answer.

This Ramadan, let it be your du‘ā’ too.

Ramadan Arrives to Remind You: You Are Not ForsakenLife may have broken things inside you — but Ramadan comes to gather the pieces.

It comes to soften what has hardened. To soothe what has been aching. To remind you that Allah has never stopped watching over you, even in the moments you felt most alone.

So if you enter this month tired, hurting, or uncertain, know this:

Ramadan is not asking you to be strong. Ramadan is asking you to be sincere.

Let this be the month where you let Allah  heal what life has worn down. Let this be the month where you learn to breathe again. Let this be the month where you discover that even broken hearts can glow in the presence of God.

heal what life has worn down. Let this be the month where you learn to breathe again. Let this be the month where you discover that even broken hearts can glow in the presence of God.

And may you leave Ramadan with a heart that feels held, softened, and gently restored — not because life became easier, but because Allah  drew you closer.

drew you closer.

I Can’t Feel Anything in Prayer – Understanding Spiritual Dryness | Night 16 with the Qur’an

The post When Ramadan Arrives To Heal What Life Has Broken appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

This series is a collaboration between Dr. Ali and MuslimMatters, bringing Quranic wisdom to the questions Muslim families are navigating.

The Confession You’re Not HearingYour teen is praying five times a day. Or trying to. Going through the motions.

But if you asked them how they actually feel during salah, here’s what they might say—if they felt safe enough to be honest:

“Nothing. I don’t feel anything. I might as well be reciting math tables.”

Most parents never hear this because most teens learn early that admitting spiritual emptiness is dangerous. It gets met with:

So, they perform. They show up to the masjid when you go. They look like they’re praying at home.

But inside? Silence.

This piece is for the parent who wants to understand what’s actually happening—and how to respond in a way that strengthens faith rather than destroying it.

First: Understand What Spiritual Dryness Actually IsSpiritual dryness is the experience of performing religious acts—prayer, dhikr, Quran recitation—while feeling no emotional or spiritual connection.

It’s not apathy. A teen experiencing spiritual dryness still cares. They’re often distressed that they don’t feel anything.

It’s not hypocrisy. A hypocrite practices outwardly while believing nothing inwardly. A spiritually dry Muslim practices while desperately wanting to feel something.

It’s the gap between action and feeling. And it’s one of the most common—and least discussed—experiences in Muslim spiritual life.

What the Prophet ﷺ Actually Said About ThisMost Muslim parents don’t know that the Prophet ﷺ explicitly addressed spiritual highs and lows as normal human experience.

Handhalah, one of the scribes of revelation, came to the Prophet ﷺ distressed. He said:

“O Messenger of Allah, when we are with you, you remind us of the Fire and Paradise until it’s as if we can see them. But when we leave you and return to our families and our work, we forget much of that.”

Handhalah thought this made him a hypocrite. That his spiritual high in the Prophet’s ﷺ presence and his spiritual low at home meant that something was wrong with his faith.

The Prophet ﷺ said:

“By the One in Whose hand is my soul, if you were to continue in that state in which you are when you’re with me and in remembrance of Allah, the angels would shake hands with you in your streets. But O Handhalah, there is a time for this and a time for that.” (Muslim)

“There is a time for this and a time for that.”

The Prophet ﷺ is saying: Spiritual peaks and valleys are part of being human. If you were spiritually elevated 24/7, you’d be an angel, not a human. And Allah created you human.

The presence of spiritual dryness doesn’t mean your teen’s faith is weak. It means they’re human.

Why Spiritual Dryness HappensThere are multiple causes, and they’re rarely purely spiritual:

Don’t say:

Why these responses fail: They all imply that spiritual dryness is a personal failure rather than a normal human experience that even the Companions went through.

What TO SayDo say:

Practical Support: What Parents Can Do

Before assuming it’s a deep spiritual crisis, check:

Suggest small changes:

Small disruptions break autopilot.

Most teens have been reciting Surah al-Fatihah since childhood. They can say it in their sleep—which is the problem.

Sit with them and go through a tafsir of Fatihah. Explain what each phrase means. What they’re asking for. Who they’re addressing.

Know what they’re saying in the prayer is the biggest game-changer for most people.

Share stories of scholars who went through dry seasons. Share your own experience if you’ve been through this.

The message: Spiritual dryness is a normal stage of faith development, not a sign of failure.

If spiritual dryness is accompanied by:

This may be depression, which requires professional help—not just more prayer.

(We’ll address this more fully in tomorrow’s discussion, insha Allah.)

Warning: When “Pray More” Makes It WorseSome parents respond to spiritual dryness by increasing religious requirements: more prayer, more Quran, more Islamic lectures.

This can backfire catastrophically.

If a teen is already feeling disconnected from prayer, forcing more of it can create:

The Prophet ﷺ warned against this:

“Make things easy and do not make them difficult. Give glad tidings and do not repel people.” (Bukhari)

If your teen is struggling spiritually, less with sincerity is better than more with resentment.

The Metric That Actually Matters

Your teen thinks the prayer where they cried was more valuable than the prayer where they felt nothing.

But that’s not how Allah measures.

Allah measures: Did they show up? Did they stand before Me even when they didn’t feel Me?

The Prophet ﷺ said: “The most beloved deed to Allah is the most consistent, even if it is small.” (Bukhari, Muslim)

Consistency while feeling nothing > intensity that fades.

The prayer your teen does when they feel spiritually dead is building their character in ways the emotionally elevated prayer never could.

Discussion Questions for FamiliesFor Teens:

For Parents:

For Discussion Together:

The Bottom Line

When your teen says “I don’t feel anything when I pray,” they’re not rejecting Islam.

They’re experiencing something the Companions and great Muslims across history experienced. Something every believer goes through.

Your job isn’t to fix it immediately. Your job is to help them keep showing up—even when showing up feels pointless.

Because the teen who learns to worship when they feel nothing is learning sincerity in its deepest form.

Continue the Journey

This is Night 16 of Dr. Ali’s 30-part Ramadan series, “30 Nights with the Quran: Stories for the Seeking Soul.”

Tomorrow: Night 17 – Is Depression Due to a Lack of Faith?

For daily extended reflections with journaling prompts, personal stories, and deeper resources, join Dr. Ali’s email community: https://30nightswithquran.beehiiv.com/

Related:

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

The post I Can’t Feel Anything in Prayer – Understanding Spiritual Dryness | Night 16 with the Qur’an appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

The US buildup before the war, Muhammad Shehada on Trump’s cruel Gaza fantasies, EU censorship and more.

The following transcript has been generated using AI, and may contain some errors that we have missed.

Every Sin Has a CureThe Illness & the Cure Series — Shaykh Ammar Alshukry

As-salāmu ʿalaykum wa raḥmatullāhi wa barakātuh.

I’m Ammar Alshukry, and I’m excited to be doing this series, in shāʾ Allāh taʿālā, in partnership with MuslimMatters, based on the incredible book by Ibn al-Qayyim: Ad-Dāʾ wa ad-Dawāʾ (The Illness and the Cure).

This is a book that scholars have long encouraged young people to read. They said that it is from the good fortune of a young person to benefit from it. Al-ḥamdu lillāh, I previously taught it as an AlMaghrib seminar called The Venom and the Serum, and I’m happy to reformat it for the MuslimMatters audience. What we’ll be doing is presenting summaries of some of the major chapters of the book.

The Question That Began the BookThe book begins with a question posed to Ibn al-Qayyim. I’ll paraphrase it:

What do the scholars of the religion say about a man who has been afflicted by a sin that he cannot leave, and he fears it will ruin his worldly life and his Hereafter? He has tried to repel it by every means, but it only grows stronger. What is the path to removing it? What is the means of escape? May Allāh have mercy on whoever helps an afflicted person.

You can see that the questioner asks with humility, includes duʿāʾ for the scholar, and references the ḥadīth:

“Allāh aids the servant so long as the servant aids his brother.”

This teaches us an etiquette of seeking knowledge: be gentle, respectful, and sincere when asking.

Ibn al-Qayyim responded not with a short answer — but with an entire book. That shows the depth of care scholars had for those seeking guidance.

The Core Issue: Struggling With DesireFrom the wording of the question, Ibn al-Qayyim understood that the person was struggling with lust (shahwah). Some scholars even inferred he may have been referring to same-sex desire.

This is why scholars say the book is especially valuable for young people — because desires often accompany youth.

The Prophet ﷺ said:

“Allāh is amazed at a young person who has no ṣabwah (inclination toward desires).”

Passion and desire are natural, but they must be guided.

Chapter One: Inspiring HopeIbn al-Qayyim begins with hope.

He reminds us that every illness has a cure, including spiritual illnesses.

The Prophet ﷺ said:

“For every disease, Allāh has created a cure.”

“O servants of Allāh, seek treatment.”

Spiritual diseases deserve even more attention than physical ones.

The First Cure: The QurʾānAllāh says in Sūrat Yūnus:

“O mankind, there has come to you an admonition from your Lord, and a healing (shifāʾ) for what is in the hearts.”

The Qurʾān is described as shifāʾ — a source of healing.

The Second Cure: Duʿāʾ (Supplication)Duʿāʾ is one of the most effective means of securing good and repelling harm.

But people often ask:

“I’ve made duʿāʾ — why hasn’t it been answered?”

Ibn al-Qayyim explains two main reasons:

1. Weakness in the Duʿāʾ ItselfThe issue may be a lack of certainty (yaqīn) or focus.

He compares duʿāʾ to a sword:

A sword is only as effective as the person wielding it. If someone is unskilled, the problem is not the sword — but the user.

The Prophet ﷺ described a traveler raising his hands in duʿāʾ, yet:

So how could his duʿāʾ be accepted?

Spiritual nourishment matters.

Abū Dharr رضي الله عنه said:

“The amount of duʿāʾ needed alongside righteousness is like the amount of salt needed for food.”

When a person is upright, even a small duʿāʾ can be powerful.

Duʿāʾ and Qadr (Divine Decree)A common confusion is:

“If everything is written, why make duʿāʾ?”

Ibn al-Qayyim explains that Allāh wrote both the outcome and the means.

We constantly try to repel one destiny with another — ignorance with education, poverty with effort. Duʿāʾ is simply another means.

The correct understanding is that duʿāʾ itself is part of qadr and can change outcomes by Allāh’s permission.

“Duʿāʾ Is Action”Shaykh Muḥammad al-Sharīf رحمه الله once said that the key to his success was duʿāʾ.

When asked, “What comes after duʿāʾ — action?” he replied:

“Duʿāʾ is action.”

Think about the things you want.

In the past seven days, how often have you sincerely asked Allāh for them?

Many people claim to make duʿāʾ, but often it is distracted and unfocused. The Prophet ﷺ said that Allāh does not respond to a heedless heart (qalb ghāfil).

Etiquettes of Powerful DuʿāʾIbn al-Qayyim lists several keys:

A present and attentive heart

The last third of the night

Between the adhān and iqāmah

After obligatory prayers

He summarizes the etiquette poetically:

A duʿāʾ made with these elements is rarely rejected.

In shāʾ Allāh taʿālā, in the next session we will discuss the belittling of sins — how even small sins can accumulate and harm the heart.

Jazākum Allāhu khayran for joining us on this journey.

Related:

[Podcast] Vulnerable Sinners vs Arrogant Saints | Sh. Abdullah Ayaz Mullanee

The post Every Sin Has a Cure | The Venom and the Serum Series appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

Wieland Hoban examines the war against Palestinians waged by the EU’s most powerful country.

I’ve been here before, standing at these gates, shaking a little—another Ramadan lies just past this doorway—but it’s never quite the same I or the same here.

Some things are the same, like the trepidation, always the trepidation—the feeling that I’m not ready. But is it not the Giver who decides on the timing of the gift and not the recipient?

I did not always see the gift, could not always put into words what it meant to me, but year after year, there was something to gain, something to learn.

As a child, I barrelled through its gates headfirst, shrieking with laughter at my big brother’s suhoor antics: tumbling out of bed minutes before fajr, bleary-eyed, glasses askew; glugging down a full pitcher of water as five younger siblings cheered him on; inhaling whatever food remained on the table; turning, with cheeks bulging, to whichever clock showed an extra minute. There were no decorations or coloured lights in my Toronto home those days, but Ramadan glowed brightly with family, good food, and a shared challenge.

As a teen, I entered its gates more mindfully, resolving to read a juz a day, along with the English translation. Despite my short-lived enthusiasm—when I fell a few days behind, I threw my hands up in defeat—it was the beginning of a journey. I let go of the timeline and puttered along anyway, taking charge of learning the message I’d only experienced secondhand. I filled the margins with pencilled-in notes, curly brackets, and underlines; my eyes and heart were opened wide; I often thought, How have I never read this before?

In my twenties, I saw Ramadan as a mirror that showed me where I was and where I needed to go. After iftar, I’d rush to get ready as family negotiations began on which mosque to visit that night, my father threatening to stay home if my siblings and I were late: If we’re going to miss ishaa, we’re not going! I found a space, those nights, when the words of God fell directly on my heart, and the world around me fell away.

There was space, too—an opening—for supplication, a direct line to request all that I wanted. The most fervent duaa, to be sure, was for a righteous spouse; Abee seemed the most difficult human on earth when it came to marriage.

Then, just like that, Ramadan came upon me as a new wife in a new land. Egypt was my parents’ homeland, Alexandria the destination of many past summers, but its energy and colour were lost on my homesick self—until Ramadan arrived with the comfort of constancy and the promise of a new beginning. Every street corner was bursting with its presence, from the gigantic metallic lanterns and strung-up lights to the recitation that filled the night and the callers who woke the sleeping for suhoor.

Another Ramadan taught me hard lessons on moderation, intuition, and respecting my body’s limits. My second child was two months old, my first a toddler; the summer fasting days were long and hot. But I tried to fast, ignoring all the ways my body was saying, This is too hard. I pushed myself, barely functioning, until my baby screamed all night because my milk had run dry. I learned that Ramadan was meant to be a mercy, not a punishment, and that exemptions were gifts from the One who knew we would need them.

As my babies grew, I learned to let go of my pre-motherhood expectations of Ramadan. I lived and breathed the knowledge that Ramadan looked different for each person, in each circumstance.

For me, it meant snatching exhausted rak’ahs while my baby wriggled on my prayer mat and, later, while my girls played pretend nearby. It meant, when I returned to Canada with my husband and girls and was working fulltime, that my living room became my masjid after I put the girls to bed. I learned that worship has many faces, some quieter and less visible than others.

Fast forward a few Ramadans, and I was back in Alexandria, where once again, lanterns and lights decorated every entrance; where recitation filled the night, voices crisscrossing on the breeze; where rows of worshippers stood under the night sky while stray cats scurried between the rows. And where, more often than not, I still pray in my own room—fighting fatigue and heavy eyes—while my daughters, now grown, each recite in separate rooms.

And I can’t help but remember the verse, And He gave you from all you asked of Him. And if you should count the blessings of Allah, you could not enumerate them. Indeed, mankind is most unjust and ungrateful.

So rejoice, my dear soul, at the gift that was not requested but desperately needed, at the blessing of another Ramadan and another breath, at meals and moments of calm, at hearts broken and bruised, yet finding healing in His words and in His promise.

Related:– My Best Ramadan – Four Stories Of Ramadans Past

– Ramadan With A Newborn: Life Seasons, Ibaadah, And Intentionality

The post The Many Faces Of Ramadan appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

This series is a collaboration between Dr. Ali and MuslimMatters, bringing Quranic wisdom to the questions Muslim families are navigating.

It’s one of the most frightening sentences a Muslim parent can hear.

Sometimes it comes directly: “I don’t know if I believe in Allah anymore.” Sometimes it comes sideways: “I don’t see the point of praying.” Or “How do we know any of this is actually true?”

And in that moment, most parents do one of two things. They panic and clamp down — increasing religious requirements, restricting freedoms, escalating surveillance of their child’s practice. Or they shut down — changing the subject, deflecting, hoping it passes.

Both responses, though understandable, are likely to make things worse.

This piece is for the parent who wants to do something different.

First: Understand what your teen is actually going through

Adolescence is, developmentally, the period in which human beings begin to distinguish what they personally believe from what they were raised to believe. This is not a Western pathology or a sign of cultural contamination. It is how Allah created human cognition to mature.

The psychologist James Fowler spent decades studying faith development across religious traditions. His research found that a period of questioning inherited belief — what he called “individuative-reflective” faith — is a normal and often necessary stage of spiritual development. Teens who never go through this stage often have what he described as “borrowed” faith: practice without ownership, compliance without conviction.

The Islamic tradition itself is not threatened by intellectual inquiry. The Quran commands reflection — tafakkur and tadabbur — dozens of times. Ibrahim ﷺ, whom Allah called Khalilullah, His intimate friend, asked Allah directly: “Show me how You give life to the dead… so that my heart may be reassured.” [Al-Baqarah 2:260] He was not rebuked. He was answered.

When your teen asks hard questions, they are not failing as Muslims. They may be on the edge of owning their faith for the first time.

The difference between doubt and rejection

Classical Islamic scholarship distinguishes between two fundamentally different internal states that can look identical from the outside.

The first is talab — seeking. The heart that says “I’m not sure, but I want to know” is a heart oriented toward truth. Ibn al-Qayyim, in Madarij al-Salikin, describes intellectual and spiritual bewilderment (hayra) as one of the recognized stations on the path of the sincere wayfarer. This kind of doubt is a sign of engagement, not departure.

The second is i’raad — turning away. This is when the heart has decided it doesn’t want an answer. It is not inquiring; it is retreating.

Most Muslim teens who express doubt are in the first category. The tragedy is that when parents respond to all doubt as if it were rejection, they can push a seeking child toward actual departure.

Your job is to keep the door of inquiry open — not slam it shut with fear.

Warning signs that this has moved beyond normal doubt

Not every expression of religious doubt is the same. While seeking doubt is healthy and developmentally normal, there are signs that a teen may need more support:

Sudden and complete withdrawal from religious practice after years of engagement, particularly when combined with other behavioral changes.

Isolation from the Muslim community and peers simultaneously — suggesting the doubt may be entangled with depression, social rejection, or identity crisis.

Expressions of shame or self-loathing around religious identity — phrases like “I’m a bad Muslim anyway” or “It doesn’t matter” — which can indicate that the doubt is less intellectual and more emotional.

Engagement with online communities explicitly designed to deconstruct Islamic belief, particularly those that combine religious critique with personal grievance or hostility.

Declining mental health markers — changes in sleep, appetite, social engagement — alongside the expressed doubt.

If several of these are present simultaneously, the doubt may be secondary to something else that needs direct attention. In that case, a trusted scholar, counselor, or if necessary a mental health professional familiar with Muslim teens, should be involved.

What to say — and what not to say

This is where most parents need the most practical help.

Don’t say:

Do say:

What your teen actually needs from you

Research on religious resilience in Muslim youth consistently points to one variable above most others: the quality of the parent-child relationship. Not the number of Islamic classes attended, not the strictness of religious rules at home — the relationship.

A teen who feels emotionally safe with you will come to you when they’re doubting. A teen who fears your reaction will manage their doubt alone, often in digital spaces with no Islamic grounding and no love for them as a person.

Your teen needs to know that your love for them is not contingent on their certainty. That you are a safe person to be confused in front of. That doubt — brought to you and brought to Allah — is a conversation you can have together.

This doesn’t mean accepting whatever conclusions they reach. It means that you remain the trusted adult in their life through the process.

The resource conversation

One of the most helpful things you can do is connect your teen to scholars and teachers who have themselves wrestled with serious questions and come out with deep, grounded faith.

Not every imam or Sunday school teacher has this capacity. Some respond to doubt with alarm, which can further isolate a questioning teen. Look for educators who combine scholarly grounding with pastoral honesty — who can say “that’s a good question, and here’s how classical scholars engaged with it” rather than “Muslims don’t ask that.”

Classical works like Ibn al-Qayyim’s Madarij al-Salikin and Ibn Rajab’s Jami’ al-‘Ulum wal-Hikam contain rich discussions of the internal spiritual life, including intellectual struggle. Contemporary writers like Jamal Zarabozo, Hamza Yusuf, Ubaydullah Evans, and others have written and spoken accessibly about faith and doubt for Western Muslim audiences.

A closing word for the parent who is themselves struggling

Sometimes when your teen expresses doubt, it touches something in you. Maybe your own faith has felt shaky in recent years. Maybe you’ve had the same questions and never resolved them.

If that’s you — you’re not alone either. And pretending otherwise doesn’t protect your child; it just models that these questions can’t be spoken.

Your teen doesn’t need a parent who has never doubted. They need a parent who takes the questions seriously and keeps moving toward Allah anyway.

That’s tawakkul. That’s Ibrahim asking the question and then watching the birds come back to life.

Discussion questions for families

Continue the Journey

This is Night 15 of Dr. Ali’s 30-part Ramadan series, “30 Nights with the Quran: Stories for the Seeking Soul.”

Tomorrow, insha Allah: Night 16 – “When Prayer Feels Empty”

For daily extended reflections with journaling prompts, personal stories, and deeper resources, join Dr. Ali’s email list: https://30nightswithquran.beehiiv.com/

Related:

Week 2 Recap: Has Your Teen’s Approach to Relationships Changed? | Night 14 with the Qur’an

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

The post When You Have Doubts About Allah | Night 15 with the Qur’an appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

From the Chagos Islands to ‘windmills’ and sharia law, the US president’s comments do not bear much scrutiny

Donald Trump has been opining about the UK again, saying on Tuesday that Keir Starmer was “not Winston Churchill” and repeating his complaint about the deal to hand sovereignty of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius. Here are some recent things the US president has said about British issues, and how they compare with reality.

Continue reading...Euractiv boss praises Trump’s belligerence.

Is Ramadan really a time to simply withdraw from the world? When we are fasting while witnessing genocides in across the Muslim world, are we really meant to turn to private worship and ignore what’s happening?

Zainab bint Younus speaks to Dr. Farah El-Sharif about what grappling with the concept of resistance in light of Islamic ethics, navigating scholarly advice to avoid politics, and the fears that many have about the consequences of engaging in resistance. This episode highlights the importance of Islam as more than just a private religious practice, and the revolutionary potential of Islamic theology in changing the world – during Ramadan, and beyond.

[This episode was recorded on February 24 and does not reflect or account for up-to-date political changes.]

Dr. Farah El-Sharif is a writer, educator and scholar in Islamic intellectual history. She received her PhD from Harvard University where she specialised in West African Islamic intellectual history. She studied with scholars in Egypt, Morocco, Senegal, Jordan and the US. You can find her writings on Substack, “Sermons at Court.”

Related:

[Podcast] The Faith of Muslim Political Prisoners | Dr. Walaa Quisay & Dr. Asim Qureshi

[Podcast] Muslims, Muslim-ness, and Islam in Politics | Celsabil Hadj-Cherif

The post [Podcast] Ramadan Is Not For Your Private Spirituality | Dr Farah El-Sharif appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

This series is a collaboration between Dr. Ali and MuslimMatters, bringing Quranic wisdom to the questions Muslim families are navigating.

For Parents:

Insha Allah, you’ve now watched (or your teen has watched) six nights of content about relationships and boundaries.

But here’s the question: Is anything actually changing?

Here’s how to tell:

Signs of Growth:

What’s NOT a sign of growth:

Transformation is slow. But it compounds.

For Teens:

You might be thinking: “I watched six videos. But, I don’t feel any different.”

Good. That’s actually healthy.

But, if you think you’ve “mastered” relationships in one week, you’re lying to yourself.

So, ask yourself:

That’s enough. That’s how change works.

Discussion Questions:

Together: How can we support each other as we move into Week 3 (Doubt, Faith & Mental Health)?

Continue the Journey:

Week 3 starts tomorrow insha Allah: Doubt, Faith & Mental Health.

Bi ithnillah, we will explore the following topics:

– Night 15: When You Doubt Allah

– Night 16: When Prayer Feels Empty

– Night 17: Is Depression a Lack of Faith?

– Night 18: When Bad Things Happen to Good People

– Night 19: When Islam Feels Like a Burden

– Night 20: Dealing with Guilt and Shame

– Night 21: Week 3 Recap

Continue the Journey

This is Night 14 of Dr. Ali’s 30-part Ramadan series, “30 Nights with the Quran: Stories for the Seeking Soul.”

Tomorrow, insha Allah: Night 15 – “I have doubts about Allah. Does that mean I’m going to Hell?”

For daily extended reflections with journaling prompts, personal stories, and deeper resources, join Dr. Ali’s email community: https://30nightswithquran.beehiiv.com/

Related:

30 Nights with the Qur’an: A Ramadan Series for Muslim Teens

The post Week 2 Recap: Has Your Teen’s Approach to Relationships Changed? | Night 14 with the Qur’an appeared first on MuslimMatters.org.

A lonely convert quits cigarettes cold turkey in Ramadan, and the brutal withdrawal becomes the fire that burns her into a new life.

Note: This is part two of a two-part story. Read Part 1

* * *

Cold TurkeyAlone in her apartment, the words “cold turkey” tolled in Mar’s head like the call of a body collector during the Black Plague: “Bring out your dead!” The phrase recalled the many attempts she’d made to quit smoking, all of which had failed: the hypnotherapist with the soft voice, the rubber band snapping against her wrist until it left welts, the week she had eaten nothing but grapefruit and smoked twice as much from hunger. The last attempt had been seven years ago. After that she’d given up and resigned herself to a life of addiction, and an early death.

It didn’t matter. She must try again, and she must succeed this time, not for herself but for Allah. For her life, her soul, her hereafter – there was an Arabic word for that, but she didn’t remember. It didn’t matter if quitting cold turkey killed her – and she believed it might. She had to rid herself of the baby god, once and for all.

The thought filled her with such terror that she sat on the bed so she wouldn’t fall.

But beneath the terror there was something else – not relief, not yet, but the faintest sense of a pale ray of sunshine breaking through a wall of iron-gray clouds. For the first time in thirty years, she had hope.

Destroying the Baby GodsHer resolve was fully formed, like a tornado that had sprung up on a summer day and was ready to tear through everything in its path. The apartment was dim, late afternoon light struggling to slip through the gaps in the smoke-stained curtains. Mar threw the curtains wide open, then went to her closet, where she dug the pack of cigarettes out of the pocket of the old winter coat. There was an entire carton under her bed, and she pulled that out as well.

It was not enough to throw them away. She could always get them out of the trash. Even if she took them to the dumpster downstairs, she wouldn’t put it past herself to go down later and climb in among the wet garbage to retrieve the cancer sticks.

She took all the cigarettes to the bathroom and kneeled over the toilet. Shaping her hands into claws, she began to destroy the beautiful, evil little sticks.

She tore the cigs apart over the toilet, letting the loose tobacco and shredded papers fall in. She flushed the toilet, then tore more cigarettes apart. Flushed. More destruction. Flushed. It was a violent, hateful, triumphant act. Yet she also felt grief. Tears spilled from her chin into the swirling water. These filthy little sticks had been her only friends for so long. They’d been there for her when everyone else had cut her off. And now she was destroying them. The sadness was almost too much to bear.

She held the lighter for a long moment. It was not a cheap disposable piece of junk, but a chrome and 14K gold luxury lighter by Dupont. Refillable. Her one luxury, purchased on credit and paid off over a three month span. It had been her gift to herself when she was promoted to supervisor. She fell to her knees and elbows on the bathroom floor, caressing the lighter with her thumbs. She loved its smooth lines and golden gleam. She brought it to her lips and kissed it sweetly, then rubbed it on her cheeks. Baby gods, she thought. Rising, she unscrewed the lighter and emptied the fuel into the toilet. Then she dropped the lighter on the floor and stomped on it viciously, again and again, until the downstairs neighbor shouted and banged on the ceiling. She picked up the mangled lighter, took the elevator down to the street, and threw it into the dumpster.

She was done. No more smoking, now and forever. No more baby god, no monkey on her back.

She went upstairs and prayed ‘Asr, and asked Allah to strengthen her for what she knew was coming. The dread was deep in her belly, as if she’d swallowed a cannonball with a short, sparking fuse, and the explosion was imminent.

If there was such a thing as damnation on earth, she was about to enter it.

WithdrawalThe first night she did not sleep at all.

Her skin crawled as if ants moved beneath it. Every position in the bed became unbearable after seconds. She threw the blanket off, dragged it back on, kicked the pillow to the floor, retrieved it again.

Her heart raced without reason. By morning her head throbbed so violently she had to crawl to the bathroom to vomit. Did that break her fast? She did not know, but she would continue fasting. It had been 18 hours since she’d smoked.

She prayed Dhuhr sitting on the edge of the bed, her back against the wall, because standing made the room tilt. The hours stretched mercilessly. Every minute seemed interminable. She was absolutely sure that insects were crawling beneath her skin. She scratched feverishly until her arms and legs bled.

She tried to read the Quran and could not hold a single line in her mind. The words blurred. She kissed the book and set it aside.

The cravings did not come as desire but commands:

Smoke now. Go down to the corner store and buy one pack. No one will know. Going cold turkey is insane, you might die. Taper off instead. You could be smoking ten minutes from now. Don’t you want that sweet relief? Who cares about the Dupont lighter, screw the lighter. Buy a cheap Bic instead. Okay, then just one cig. One only, what’s the harm? You’re sick, you have an excuse to break your fast.

And on and on.

Thirty hours without a cig. She lay in bed, curled on her side, and pressed her forehead into the headboard until a towering wave of nausea passed. Her head was splitting down the middle, as if an axe were buried in her skull.

Saturday she did not open the curtains.

Sunday she left the apartment only once, for a frozen burrito and a bottle of apple juice for iftar. The walk to the corner store felt like crossing a desert.

“The usual?” the store clerk asked. Young man with curly blond hair. Surfer type. Healthy. Definitely not a smoker, nor a Muslim. So not one of her people on either count.

“What do you mean?” Her voice came out hoarse.

The cashier studied her with open concern. She hadn’t brushed her hair, and might even have dried vomit on one cheek.

“Your usual brand,” the clerk elaborated. “Filtered, extra long. Two packs?”

The question pierced her. She almost stumbled backward. But instead she put the money on the counter, her hand shaking violently.

“No cigs,” she said. “Just the food.”

Understanding dawned in the clerk’s eyes. He gave her a supportive nod and returned the change.

Trial By FireShe called in sick to work. “I have the flu,” she told her supervisor’s voicemail, her voice raw and unrecognizable. She took the entire week off.

The nausea, muscle cramps, and dizziness were constant. Pain seeped into her bone marrow. She would have gone to the hospital if she could have gotten out of bed. Yet she continued her Ramadan fast. She’d always considered herself a weak person, someone with no grit, no reservoir of willpower. Yet through it all she continued fasting, like a dog gripping a bone in its jaws, not letting anyone take it away.

Her phone lay beside her like a dead thing. No one called, neither from work nor from the masjid. On Wednesday she was too sick to attend the converts meeting. She felt terrible about it, because she’d promised that charming couple, Layth and Khadijah, that she would be there. Mar had not taken Khadijah’s phone number – she wasn’t brave enough to ask – and had no way to contact them. They would think she’d flaked on them. They were the only people who’d shown her any kind of friendship, and she’d ruined it already.

When she had the energy she read the Quran. When she didn’t, she listened to it on her phone, and it soothed her like water poured over a parched desert plant. The sound of the recitation, even when she did not understand, was honey to her soul.

Thursday she had a massive fit of nausea during the daytime hours, throwing up again and again, until all that came up from her gut was thin streams of liquid.

She got Imam Ayman’s number from the masjid website and called.

“As-salamu alaykum. This is Mar.”

“Sister Maria?” His voice was uncertain. “You sound different.”

She suppressed a surge of irritation that he still didn’t know her name. “It’s Mar, not Maria. Does vomiting break the fast?”

“If it’s unintentional, no. But if you make yourself vomit intentionally, the fast is broken and you must make up the day.”

“Why would I make myself vomit on purpose? I was sick, that’s all.”

“Yes, sorry. Sister Maria – I mean Mar. Are you okay?”

“Thanks brother Imam.” She hung up the phone.

Personal ProblemsAn hour later sister Juana called. “Ayman was worried about you. Is there anything I can do for you?”

Mar hesitated. “Personal problems,” she said finally, and hung up the phone.

She woke from a nap and noticed a slip of paper under her door. “I knocked but no one answered. Hope you are alright. Enjoy the halal food. – Juana.”

She opened the door and found a covered dish filled with chicken taquitos. She didn’t know how Juana had gotten her address, until she remembered filling out a contact form at a masjid fundraiser her second week there. She put the dish in the fridge. She felt something. Not gratitude. More like a spark of hope that someone actually cared. The married couple, and now Juana. It was something to hold on to, for now.

Passing of the StormThat relentless vomiting fit was rock bottom. After that the physical agony began to recede. The tremors stopped, and the headaches faded. Her lungs ached, however, and she began to cough heavily. She coughed up gob after gob of dark mucus. She was terrified that her lungs might be coming apart, she might be coughing up pieces of the tender tissue.

The cravings were not gone, but they came now like dark whispers rather than forceful commands.

She felt utterly emptied out. Weak, yes, but mostly just limp and half-broken, as if she had run a marathon, and at the finishing line had been beaten up by a biker gang. It had been nine days since she’d smoked a cigarette. She had never done this before in her adult life. Had never believed she could. If miracles happened to ordinary people, then it was a miracle.

Her appetite returned. She ate some of Juana’s taquitos. They were good. She almost imagined she could taste them, but that was wishful thinking. Her taste buds were dead.

On Monday she was well enough to go to work. The coughing persisted, so she wore a mask. At mid-morning, after catching up on emails, she summoned Sarah Kim to her office.

The young woman stood in front of her, guarded.

Mar rose from her chair, approached the young woman. “I need you to be honest,” she said. “Do I still stink?”

Sarah blinked, caught off guard. She hesitated, then stepped closer and inhaled tentatively. Her nose wrinkled immediately.

“Yes,” she said, almost apologetically. “It’s… in your clothes. And your hair too, I think.”

Mar nodded once, her lips pursed. “Thank you for your honesty.”

The PurgeThe discount clothing store was harshly lit and nearly empty. She bought everything in practical colors and sizes. Skirts long enough for salat, loose blouses with long sleeves, underwear, socks. A coat and scarf. A new pair of shoes.

At home she showered and put on the new clothes immediately, the fabric still stiff. Then she began throwing everything out. Every article of clothing she owned went into trash bags. She emptied the closet and dresser, and dumped the dirty clothes out of the laundry hamper.

Then she turned her attention to the linens. Sheets and pillowcases, towels, and even the shower curtain went into trash bags. Maghreb arrived. She broke her fast on a bean burrito and apple juice, prayed Maghreb and went back to work. When she was done there were six full trash bags on the floor.

She carried them down to the dumpster in three trips, her arms shaking from the weight, and threw them in without looking back.